Culture & Ethics

Culture & Ethics

Faith & Science

Faith & Science

Wordsworth: Disciples at Home and Abroad

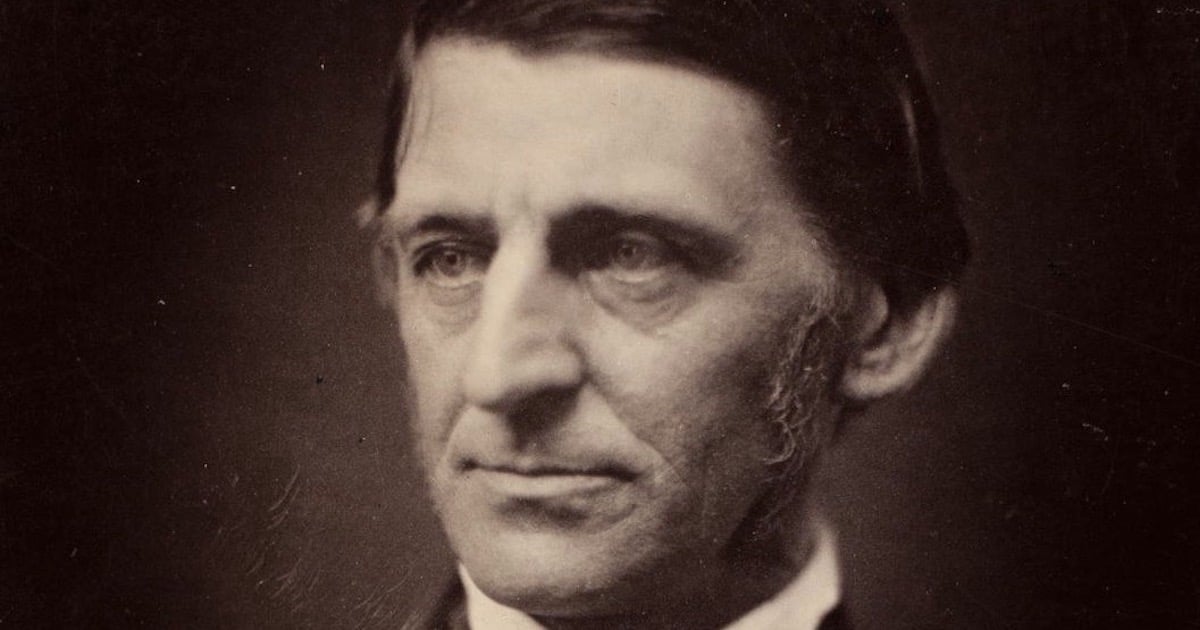

In a series of posts I am exploring the competing visions of nature in the work of William Wordsworth and Charles Darwin (find the full series here). I have already described the conception of Wordsworth which was presently to radiate outwards from the British Isles. In 1848 Ralph Waldo Emerson is on record as having paid a return visit to the then aged Wordsworth. Emerson would go on to shape the thinking of Henry David Thoreau who developed a distinctly American strain of Romantic retreat in the woods of Walden.

The American philosopher William James was an admirer of Myers’s exegesis of Wordsworth, and like Mill, reported being “restored to sanity” by his reading of the poet. Impatient of the old three-tier universe (Heaven, Earth, Hell in descending order) traditional to an older Christian cosmogony, James saw the religious instincts of mankind as being situated largely in the subconscious, its apprehensions mediated by the “still small voice” independently of any particular belief system.

A Subjective Apprehension

Overall, Wordsworth’s achievement might be described as that of having given currency to the belief that religious feeling had its origins in a subjective apprehension of the sacred. Matthew Arnold stated that, whereas religion had previously depended on creeds and supposed facts, Wordsworth’s bold conception of poetry as “the breath and finer spirit of all knowledge” was to gain traction, even to the extent of challenging the sole authority of the Bible in mediating truth. Turning orthodoxy on its head, a reading of Wordsworth encouraged the idea that the genesis of religion lay in essentially mystical apprehension. Such was essentially the conception which underlay William James’s The Varieties of Religious Experience (1902)1 and German theologian Rudolf Otto’s Das Heilige / The Idea of the Holy (1917).2 Otto for instance defined God as an awe-inducing power, something ganz andere (wholly different) to normal categories of human experience — a presence which can be apprehended but not defined in precise conceptual terms.

The Romanian-American scholar of world religions, Mircea Eliade, would later endorse this non-doctrinal definition of God. For Eliade religion is a primal experience: “It is not a matter of theoretical speculation, but of a primary religious experience that precedes all reflection on the world.”3 Eliade invoked the concept of cosmic sacrality, the idea that Nature in its entirety is little less than a “hierophany.” Wordsworth undoubtedly played a seminal role in the evolution of that conception in European and North American thinking since his poetry has the irresistible effect of resacralizing what was even by his own day starting to become a desacralized world.

Next, “The Apotheosis of William Wordsworth.”

Notes

- William James, The Varieties of Religious Experience [1902] edited by Martin E. Marty (London: Penguin, 1982).

- Rudolf Otto, The Idea of the Holy, trans J. Harvey (Oxford: OUP), 1958.

- Mircea Eliade, The Sacred and the Profane: The Nature of Religion [1957] (New York: Harcourt, 1968) p. 21.