Evolution

Evolution

Paleontology

Paleontology

Fossil Friday: Cambrian Bryozoa Come and Go

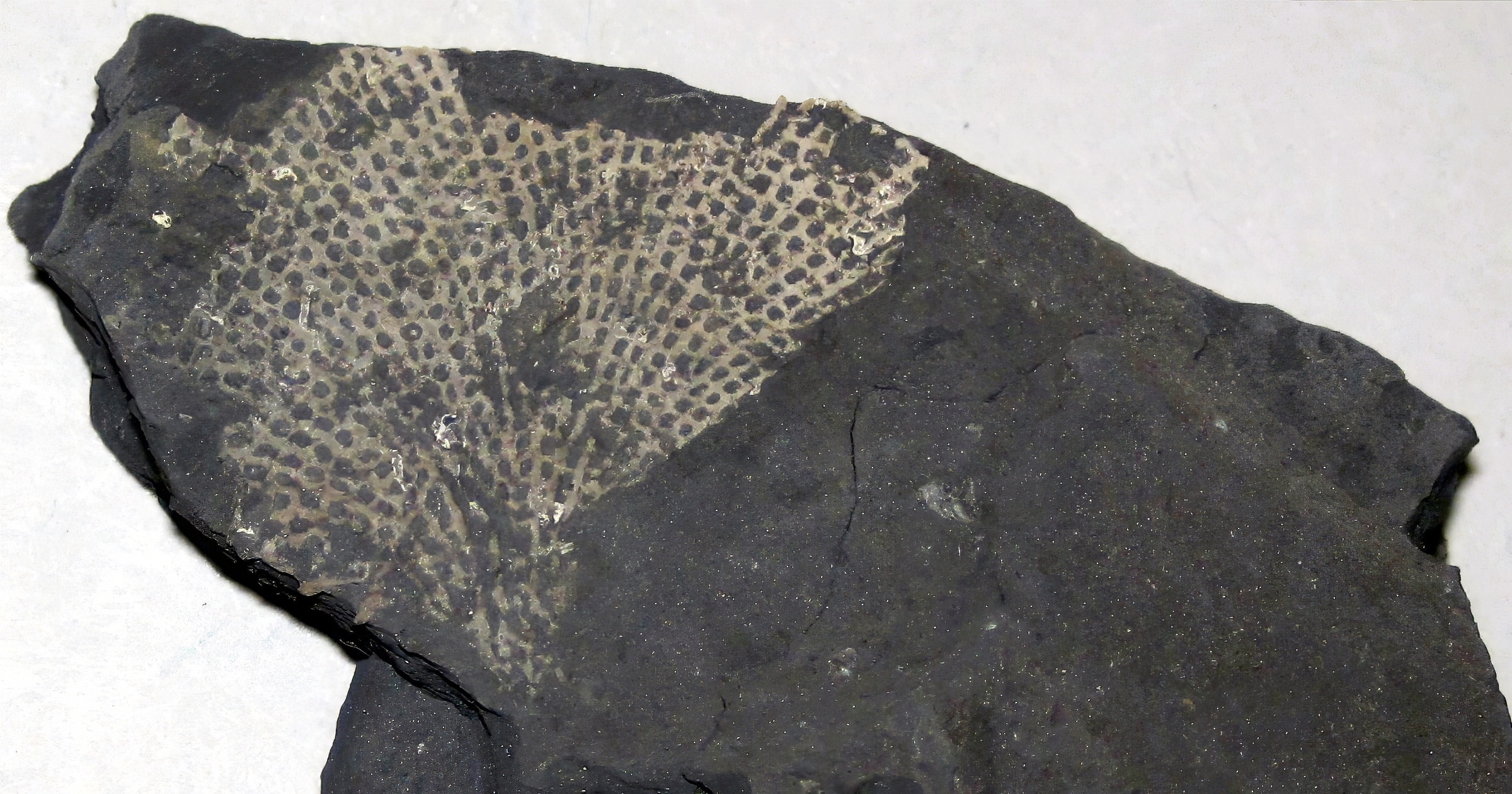

Bryozoa or moss animals are a phylum of bilaterian animals with a distinct body plan and controversial relationship. The 6,500 living species are mostly marine, colonial invertebrates in which each zooid bears a crown of delicate tentacles as a filter-feeding organ, which is called lophophore. Uncontroversial fossil bryozoans are known since the Lower Ordovician (Ma et al. 2015) and, for example, abundant in Carboniferous strata, such as featured fenestrate bryozoan from the Middle Pennsylvanian of Ohio. Even though molecular clock studies predicted the origin of Bryozoa in the Cambrian (Ernst & Wilson 2021, Zhang et al. 2021), until recently they represented one of the few major animal phyla not yet recorded from Lower Cambrian fossils. This was believed to have some evolutionary implications because some animal body plans would have originated after the Cambrian Explosion. Some early candidates for Cambrian bryozoan fossils (Elias 1954) have later been discredited (Riding 2000). However, in the past 23 years two plausible candidates have been suggested for Cambrian Bryozoa, i.e., the genera Pywackia and Protomelission.

Strong Arguments but Doubts Persist

Pywackia baileyi was described by Landing et al. (2010) as a cryptostome/stenolaemate bryozoan from phosphatic fossils from the Late Cambrian of southern Mexico, which placed the origin of all skeletized metazoan phyla in the Cambrian. Taylor et al. (2012, 2013, also see Wilson 2012) disputed this interpretation and considered Pywackia as a pennatulacean octocoral. Ma et al. (2015) agreed with this determination as an octocoral. Landing et al. (2015, 2018) rejected this new interpretation and commented that the authors “have not addressed the histologic similarity, budding method, and 14 named homologies of P. baileyi to stenolaemate bryozoans and not to octocorals. Nor have they explained the extreme downward range extension (420my) of confidently established pennatulacean octocorals that otherwise first appear in the Late Cretaceous to the late Cambrian P. baileyi.” These are quite strong arguments. Nevertheless, the doubts were reinforced by a new study of the skeletal microstructure and taphonomy of Pywackia, which suggested that a bryozoan identity is unlikely, and they rather represent algae, chordates, or octocorals (Hageman 2018). That is quite a wide range of very different alternative determinations! The study was formally published this year (Hageman & Vinn 2023) and now suggested that “Pywackia likely represents a rare, minor clade in an otherwise unknown cnidarian group, possibly, but not directly related to conulariids, octocorals, and/or tabulates.” The authors also mention similarities with dasyclad green algae and with primitive chordates. Landing and co-authors have not yet responded but will likely disagree.

Protomelission gatehousei was described by Brock & Cooper (1993) from Australian limestone fossils. The authors noted a similarity with bryozoans but did not formally attribute the problematic fossils to any known group of animals, which was concurred by Landing et al. (2018). Zhang et al. (2021) studied additional phosphatized specimens from South China with microCT and identified them as Cambrian Bryozoa (also see Brock & Strotz 2021 and Zhang 2021). This was widely reported as a breakthrough that “allows scientists to start piecing together the early evolutionary history of these over-looked creatures” (Ashworth 2021, Ernst & Wilson 2021). However, this year Protomelission suffered the same fate as Pywackia. A new study (Yang et al. 2023) challenged the determination as bryozoan and suggested it rather is a dasyclad green alga, thus a seaweed instead of an animal (see Ashworth 2023 and Lesté-Lasserre 2023), so that “there remain no unequivocal bryozoans of Cambrian age.”

But All Is Not Lost for Cambrian Bryozoans

Last year, Pruss et al. (2022) published a study that describes a possible palaeostomate bryozoan from the Lower Cambrian of Nevada. The authors also followed the interpretation of Protomelission as soft-bodied bryozoan. This year, two new metazoans have been described by Zhao et al. (2023) from the Cambrian Guanshan biota of China. One is an unnamed cnidarian-like metazoan and the other a likewise unnamed putative bryozoan. The authors suggested that “The new material will represent the earliest known bryozoans from the Burgess Shale-type Lagerstätten and indicate that some representatives of Bryozoa were adapted for attaching to hard substrates in siliciclastic environments during Cambrian Stage 4.”

Overall, the evidence for Cambrian bryozoans is accumulating more and more and thus adding another phylum to the abruptness of the Cambrian Explosion. But even if all the supposed Cambrian bryozoans should turn out to be based on misidentifications, the phylum Bryozoa would still have “bursted into existence” (Brock & Strotz 2021) with the Great Ordovician Biodiversification Event (GOBE), which has been called life’s second Big Bang (O’Donoghue 2008). Either way, the scientific debate shows how difficult and uncertain the identification of such fossils can be, so that all claims have to be taken with a grain of salt. This does not just apply to alleged Cambrian bryozoans but more generally to many if not most claims in paleontology. It is a field that often has more in common with the interpretation of inkblots in Rorschach tests than with hard science, and it is especially prone to a dangerous blurring of the line between primary hard evidence (data) and biased interpretation of the latter. This, and of course the inconvenient conflicting evidence from the discontinuities in the fossil record, may be the main reasons why paleontology did not reach the “high table” of evolutionary biology (Prothero 2009).

References

- Ashworth J 2021. Ancient bryozoan fossil solves one of early life’s greatest mysteries. Natural History Museum Science News October 27, 2021. https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/news/2021/october/ancient-bryozoan-fossil-solves-one-of-greatest-mysteries.html

- Ashworth J 2023. New fossils challenge the identity of the oldest bryozoan. Natural History Museum Science News March 8, 2023. https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/news/2023/march/new-fossils-challenge-identity-oldest-bryozoan.html

- Brock GA & Cooper BJ 1993. Shelly fossils from the Early Cambrian (Toyonian) Wirrealpa, Aroona Creek, and Ramsay Limestones of South Australia. Journal of Paleontology 67(5), 758–787. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022336000037045

- Brock GA & Strotz L 2021. The bryozoan mystery: a new look at an old fossil reveals the origin of these tiny coral-like creatures. The Conversation October 27, 2021. https://theconversation.com/the-bryozoan-mystery-a-new-look-at-an-old-fossil-reveals-the-origin-of-these-tiny-coral-like-creatures-170261

- Elias MK 1954. Cambroporella and Coeloclema, Lower Cambrian and Ordovician bryozoans. Journal of Paleontology 28(1), 52–58. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1300207

- Ernst A & Wilson MA 2021. Bryozoan fossils found at last in deposits from the Cambrian period. Nature 599(7884), 203–204. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-021-02874-z

- Hageman SJ 2018. Pywackia is not a Cambrian Bryozoan: Evidence from Skeletal Microstructure and Taphonomy. GSA Annual Meeting in Indianapolis, Indiana, USA – 2018, Paper No. 272-7, Abstract. https://gsa.confex.com/gsa/2018AM/webprogram/Paper319226.html

- Hageman SJ & Vinn O 2023. Late Cambrian Pywackia is a cnidarian, not a bryozoan: Insights from skeletal microstructure. Journal of Paleontology. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/jpa.2023.35

- Landing E, English A & Keppie JD 2010. Cambrian origin of all skeletalized metazoan phyla – Discovery of Earth’s oldest bryozoans (Upper Cambrian, southern Mexico). Geology 38(6), 547–550. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1130/G30870.1

- Landing E, Antcliffe JB, Brasier MD & English AB 2015. Distinguishing Earth’s oldest known bryozoan (Pywackia, late Cambrian) from pennatulacean octocorals (Mesozoic–Recent). Journal of Paleontology 89(2), 292–317. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/jpa.2014.26

- Landing E, Antcliffe JB, Geyer G, Kouchinsky A, Bowser SS & Andreas A 2018, Early evolution of colonial animals (Ediacaran Evolutionary Radiation–Cambrian Evolutionary Radiation–Great Ordovician Biodiversification Interval). Earth-Science Reviews 178, 105–135. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2018.01.013

- Lesté-Lasserre C 2023. Fossil thought to be earliest bryozoan animal may actually be seaweed. NewScientist March 8, 2023. https://www.newscientist.com/article/2363472-fossil-thought-to-be-earliest-bryozoan-animal-may-actually-be-seaweed/

- Ma J-Y, Taylor PD, Xia F & Zhan R 2015. The oldest known bryozoan: Prophyllodictya (Cryptostomata) from the lower Tremadocian (Lower Ordovician) of Liujiachang, southwestern Hubei, central China. Palaeontology 58(5), 925–934. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/pala.12189

- O’Donoghue J 2008. The Ordovician: Life’s second big bang. NewScientist June 11, 2008. https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg19826601-700-the-ordovician-lifes-second-big-bang/

- Prothero D 2009. Stephen Jay Gould: Did He Bring Paleontology to the “High Table”? Philosophy, Theory, and Practice in Biology 1(1): e001, 1–7. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3998/ptb.6959004.0001.001

- Pruss SB, Leeser L, Smith EF, Zhuravlev AY & Taylor PD 2022. The oldest mineralized bryozoan? A possible palaeostomate in the lower Cambrian of Nevada, USA. Science Advances 8(16): eabm8465, 1–8. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abm8465

- Riding R 2000. Calcified Algae and Bacteria. pp. 445–473 in: Zhuravlev A & Riding R (eds). The Ecology of the Cambrian Radiation. Columbia University Press, New York (NY), 536 pp. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7312/zhur10612-020

- Taylor PD, Berning B & Wilson MA 2012. Is the world’s oldest bryozoan actually the world’s oldest pennatulacean? Palaeontological Association 56th Annual Meeting, Dublin, Ireland, Programme and Abstracts, 52.

- Taylor PD, Berning B & Wilson MA 2013. Reinterpretation of the Cambrian ‘Bryozoan’ Pywackia as an Octocoral. Journal of Paleontology 87(6), 984–990. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1666/13-029

- Wilson M 2012. Cambrian bryozoans? Not yet! Wooster Geologists December 2012. https://woostergeologists.scotblogs.wooster.edu/2021/10/27/cambrian-bryozoans-not-yet/

- Yang J, Lan T, Zhang X-G & Smith MR 2023. Protomelission is an early dasyclad alga and not a Cambrian bryozoan. Nature 615(7952), 468–471. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-05775-5

- Zhang Z 2021. A Cambrian origin for the colonial phylum Bryozoa. Nature Ecology & Evolution Community October 27, 2021. https://ecoevocommunity.nature.com/posts/a-cambrian-origin-for-the-colonial-phylum-bryozoa

- Zhang Z, Zhang Z, Ma J, Taylor PD, Strotz LC, Jacquet SM, Skovsted CB, Chen F, Han J & Brock GA 2021. Fossil evidence unveils an early Cambrian origin for Bryozoa. Nature 599(7884), 251–255. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-04033-w

- Zhao J, Li Y & Selden PA 2023. Two new metazoans from the Cambrian Guanshan biota of China. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 11, 1–7. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2023.1160530