Intelligent Design

Intelligent Design

Medicine

Medicine

My Briar Patch: Notes of a Country Doctor

At the outset I wish to express my deep appreciation to Daniel Witt for his excellent Evolution News post of September 9, wherein he summarized many of my contributions to this page, a series on the science of purpose, and juxtaposed them with the work of Stuart Kauffman. I was humbled to find myself compared with Kauffmann, a world-famous theoretical biologist. Thirty years ago, when I was still trapped in my own mechanistic prison, Kauffman’s writing opened important doors that allowed me to begin to see the world in a new light. Although I was still within a materialist framework, it was one of my first steps toward a larger vision.

But the mere fact that the two of us could be compared at all is really the much more important point. It is true that we are both MDs and in fact graduated from the same medical school, the University of California at San Francisco. Kauffman preceded me by 11 years. As part of our medical education, Kauffman and I shared in a crucial formative experience: we both came of age during a unique time in the history of science: the so-called Biologic Revolution of the 1960s and 1970s. This was the era of Nobel Prize-winners James Watson, Francis Crick, and Jacques Monod. Crick and Monod devoted much of the remainder of their careers to establishing the foundation of modern-day scientific atheism. As young medical school graduates, both Kauffman and I were fully indoctrinated in the mechanistic consensus, which asserts that all organisms, including humans, are biologic machines without souls.

Two Paths Diverge

But from that point early on in our careers, there was a profound divergence. According to his Wikipedia biography, Kauffman went straight into research and never looked back. By contrast, I have immersed myself in the clinical experience, treating cancer patients at the bedside now for 45 years.

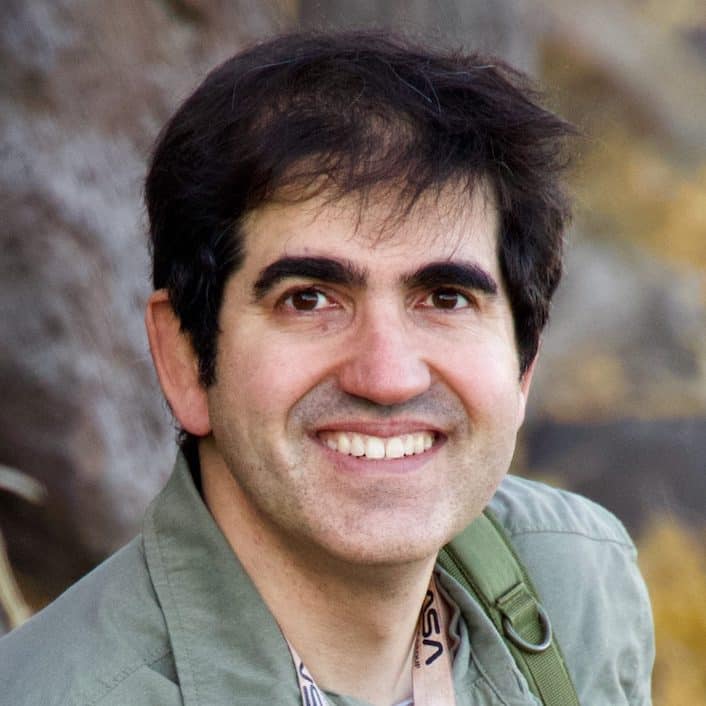

I am a small-town country doctor in his eighth decade who has spent 99 percent of his working hours toiling in the care of the sick. How could someone so distantly removed from academia ever conjure a theoretical framework regarding the science of purpose worthy of mention, even remotely, in the same context with the work of Professor Kauffman? He has been a giant in this field for over fifty years.

It took me about twenty years after medical school to break free of the intellectual “comfort” afforded by the mechanistic consensus. For those interested, my journey is chronicled in my first book, The Undying Soul: A Cancer Doctor’s Discovery. It was during those years as a community cancer doctor, constantly engaged in the struggle of patient versus cancer, that I did discover something worth writing about. And it is that something that marks the most profound difference between Professor Kauffman and myself.

The Art of Medicine

Practicing doctors often describe what they do as the art of medicine. Not unlike painting or playing the piano. You can read all about it but you cannot actually do it until you practice it. But the same is not quite as true for theoretical science. So yes, I could read all of Kauffman’s writings and all of the work of his contemporaries, both his critics and his acolytes. And in my rare spare time, I could think deeply about the questions we are both interested in, i.e., the role of purpose in life and in biology. Still, I was for the most part alone in my quest. I certainly did not have the advantage of daily interaction with others in the field with whom to converse and exchange ideas.

Which brings us back to the main question. How could I compete?

As I have said more than once in the posts in this series, my main goal has been to synthesize and thereby reinvigorate, or otherwise creatively contextualize, the brilliant work of others. This type of synthesis is itself a skill, but it is far less an accomplishment than deriving original concepts. Yet, it has been by this method that I have been able to perhaps, as Daniel Witt so graciously suggests, stay up to speed with the eminent professor. I am by no means “standing on the shoulders of giants.” I have just been taking assiduous notes at the feet of the masters.

The Sacred Space

But there is one thing that I like to think I have mastered. It is something to which Professor Kauffman apparently has not had access. It has been referred to as the sacred space between doctor and (cancer) patient. I began my career resolutely adherent to materialism. But after countless interactions with cancer’s crucible, I finally learned to see and touch the human soul. It was from there that I began my quest to describe what precedes science and materialism. My experience as an oncologist thus taught me the reality of the spiritual realm.

There is an old adage, “The biggest fool can ask a question that the wisest man cannot answer.” More to the point, if you start a line of inquiry based on false assumptions, you can never answer your question, no matter how brilliant you might be. Take for example the millennial confusion of “wandering stars,” aka planets, which could only be finally solved when the paradigm of geocentrism was replaced with heliocentrism.

A Famous Phrase, Reversed

In his remarkable article Daniel Witt points out that no matter how hard Kauffman tries, he still comes up empty. And that is because he is stuck in the wrong paradigm. Primary knowledge must precede the subject-object metaphysics we inherited from René Descartes. Descartes, one of the founding fathers of Western science, led us into the wrong paradigm, from which we must now be liberated. Because what he famously said was exactly 180 degrees off course. The correct statement should have been, “I am, therefore I think.” As pointed out by UC Berkeley professor of philosophy John Searle, “Philosophy never completely overcomes its history, and many of the mistakes in the past are still with us.”

That is why, when Kaufmann invokes his materialist paradigm to explain the origin of purpose in organisms, his arguments are necessarily circular. Purpose was excluded from the materialist paradigm from its inception, which is why it is not reducible to it. As a result, Kauffman, as brilliant as he is, can never solve the problem. It reminds me of that wonderful scene in Disney’s Song of the South, where Br’er Fox can never find Br’er Rabbit because he hides in the briar patch, a place Br’er Fox refuses to look. Put most simply, a square peg will never fit into a round hole. Ever. It does not take a genius to understand that. But someone who thinks he is a genius might still spend a lifetime trying to find a way.

Immanent Purpose

So now you can see that my competition with Professor Kauffman, and perhaps even championing him in the comparison, had less to do with how much each of us knows about the subject, but rather which of one of us was inspired to choose the correct paradigm. In my chosen paradigm, described in detail in my second book, Telos, purpose is immanent, not derivative.

My inspiration for the telos paradigm comes from the privilege of witnessing the grace and courage of those afflicted with life-threatening illness. That’s what a practicing doctor does. It’s a vastly different experience from that of the laboratory or the lecture hall. Most importantly, patient care is directly connected to life itself, the briar patch where Br’er Rabbit is hiding. That is where you have to look.