Intelligent Design

Intelligent Design

Fairy Circles, Spider Silk, Epigenetics, and More: Intelligent Design in the News

We update the apps on smartphones (or let them update automatically). Science news is like that; new findings or corrections keep coming. It’s a good sign when ongoing research continues to support a theory. If intelligent design were a bad theory, it would be right to expect its arguments to lose power over time. That is not the case. The usefulness of ID in scientific research grows stronger each passing year.

What’s been happening with design stories covered in the past by Evolution News? Here’s a roundup of subjects with updated information.

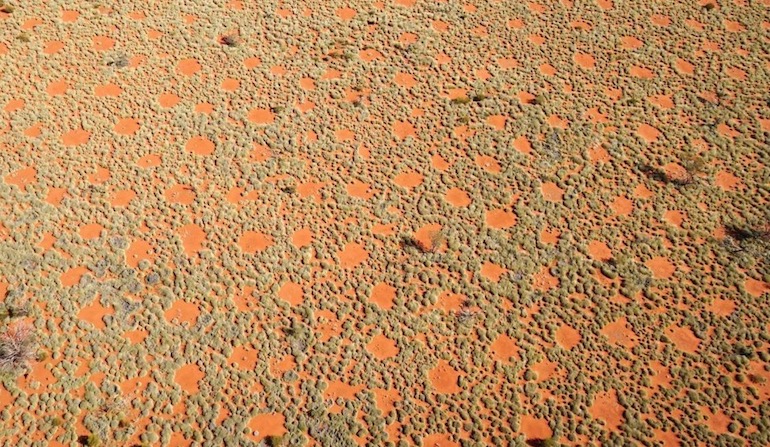

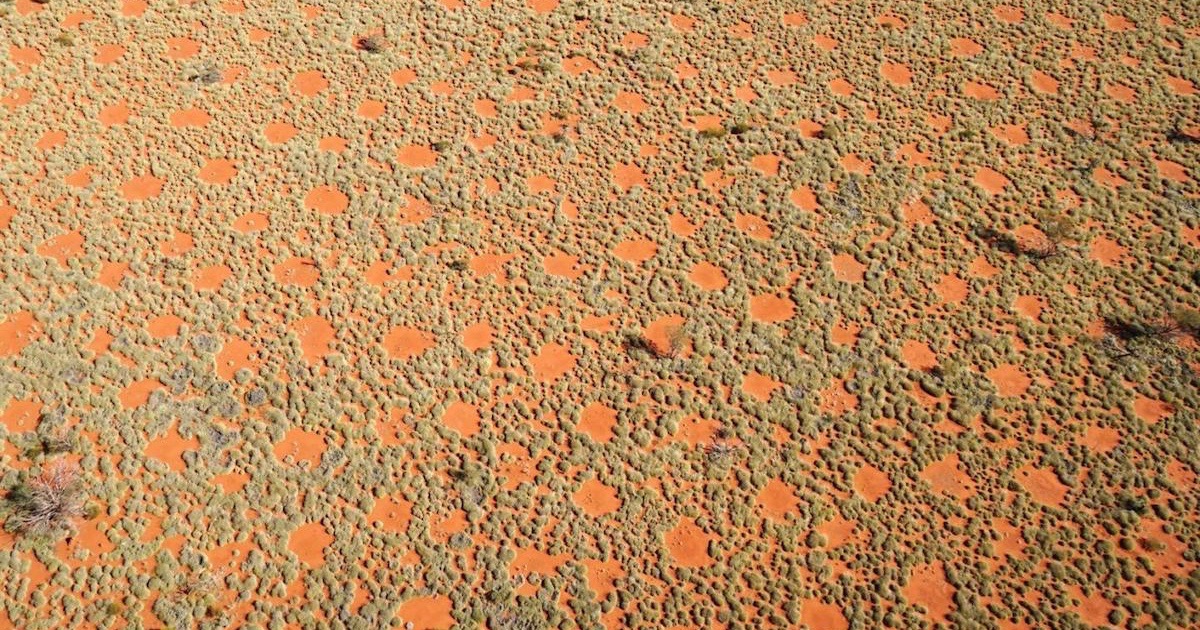

Fairy Circles

In October 2016, Evolution News looked at unusual formations in Africa and Australia to see how the design inference can be applied to unexpected phenomena. So-called “fairy circles” yielded to a natural explanation, according to a research team: they are abandoned termite mounds. Now, however, another natural theory is rising. A team from the University of Göttingen disputes the termite theory, and claims they are caused by clay soil compacted by rain. So in fifty years since the Namibian circles came to attention, and in five years since the Australian ones were discovered, scientists still argue about competing explanations.

As pointed out here in September 2017, fairy circles, which intuitively are natural but hard to explain, are easily distinguished from crop circles and radial irrigation systems, which we know are intelligently designed. Whatever becomes of this interesting case of science seeking an explanation, it shows that the design inference would be useful to aliens with logical minds scanning the surface of the Earth.

Spider Silk

In July 2017, reporting here took a closer look at spider webs. The silk that spiders produce has long been an icon in the field of biomimetics. The material is flexible yet strong, inspiring materials scientists to try to imitate it. Now, another property has come to the attention of scientists at MIT. They found that at about 70 percent relative humidity, dragline silk undergoes a unidirectional twisting motion. Since silk is protein-based, they tried to figure out what was changing. It turns out that the amino acid proline, in one of the two primary proteins, breaks its hydrogen bonds when exposed to humidity, leading to the twisting motion. Although they don’t understand the biological significance of this property, they see gold in applications:

This is a fantastic discovery because the torsion measured in spider dragline silk is huge, a full circle every millimeter or so of length… This is like a rope that twists and untwists itself depending on air humidity. The molecular mechanism leading to this outstanding performance can be harnessed to build humidity-driven soft robots or smart fabrics. [Emphasis added.]

Their paper in Science Advances points to potential applications from this “torsional actuator driven by humidity.”

Bird Brains

In June 2016, Evolution News proposed using “bird brain” as a compliment. Our “feathered friends come well equipped with hardware and software for complex behaviors,” it was noted here at the time. Now, welcome parrots to the bird Mensa society. Cognitive psychologists at Harvard have demonstrated that parrots can pass a classic test of intelligence. According to their research, “an African grey parrot named Griffin is rewriting the rules when it comes to avian intelligence” because it can pass logical tasks equal to the intelligence of a five-year-old child. In fact, the bird did better than apes! Could this have the effect of rearranging some branches on the evolutionary tree?

Rubisco

In June 2017, an article here explored the wonders of a molecular machine named Rubisco (short for Ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase). Rubisco has the remarkable ability to discriminate between carbon dioxide and molecular oxygen. Moreover, the machine “may be nearly perfectly optimized” for this task, which exudes oxygen during photosynthesis. Scientists knew that rubisco is the most abundant protein on Earth, but they were surprised to find recently that their estimates were off by an order of magnitude. Scientists at the Weizmann Institute now figure that this carbon fixing enzyme is “10 times more abundant than previously thought.” The biosphere functions, one may infer, because of an optimized molecular machine.

Whales

Who can forget the songs of humpback whales, like those heard in the Illustra documentary Living Waters? The beast’s acoustic range is phenomenal, from soprano squeals to infrasonic grunts. Scientists have recorded more songs, made only by the males, and found that they sing more than thought. They don’t only sing in tropical waters during mating season, but continue singing when high food availability allows some to overwinter in Arctic sites, according to Science Daily. “The research suggests that humpback whale singing is a more flexible behavior than previously thought and can occur at overwintering feeding sites as well as traditional breeding grounds.” Their open-access paper can be found at PLOS ONE.

Blue whales, the largest animals on Earth, have good memories, says Phys.org. They can “almost perfectly match the timing of their migration to the historical average timing of krill production, rather than matching the waves of krill availability in any given year.” This tends to put them in the “Goldilocks zone” for feeding success. “These long-lived, highly intelligent animals are making movement decisions based on their expectations of where and when food will be available during their migrations,” a NOAA researcher commented. Be glad these massive creatures rely on two-inch krill for food. “Blue whales can grow to the length of a basketball court, weigh as much as 25 large elephants, and their mouths can hold 100 people,” the article notes.

Epigenetics

Earlier this year (January 19), reporting here relayed examples of epigenetic activity in various organisms. A new study from the University of Sheffield finds that plants have the ability to pass along immune responses to their offspring via mechanisms unrelated to Darwinian processes of DNA mutation and selection.

Scientists have debated for years whether and how plants are capable of passing on defence traits to their offspring via epigenetic mechanisms — we hope that our study helps to add clarity to the field of epigenetics, which in many ways can be regarded as ‘the dark matter of biology’. We also hope that our study motivates translational research to determine how far epigenetics can be exploited in the global fight against plant diseases.

Proteasomes

In September 2016, Evolution News called attention to quality control in the cell’s trash pickup. This year, Florida State researchers think that a “New clue for cancer treatment could be hiding in microscopic molecular machine,” the proteasome. Look how they describe it: “Buried deep within the dazzlingly intricate machinery of the human cell could lie a key to treating a range of deadly cancers, according to a team of scientists at Florida State University.” Look what’s involved in the assembly of these machines:

Proteasomes collect those unneeded, damaged or defective proteins and decompose them into amino acid building blocks, which are subsequently repurposed for the production of new proteins. Proteasomes are assembled from more than 60 protein subunits, “however, they don’t just form spontaneously from these parts,” Tomko said.

“They require assistance from dedicated helper proteins called assembly chaperones,” he said. “These chaperones act as factory workers to build proteasomes. Once the proteasome is built, the chaperones have to release it so that it can function properly and they can then begin work on the next one.”

Monarch Butterflies

Everyone who loves the story of monarch butterflies, shown so beautifully in Metamorphosis, is saddened by their rapid declines in numbers. The typical narrative blames genetically modified crops that allow for spraying of pesticides that kill milkweed, on which the butterflies depend for laying their eggs. Now, however, a study by three researchers at UCLA, published in PNAS, says that the decline in population began long before GM crops were introduced. By studying museum records and herbaria samples going back to 1900, they found the decline began around 1950.

Herbicide-resistant crops, therefore, are clearly not the only culprit and, likely, not even the primary culprit: Not only did monarch and milkweed declines begin decades before GM crops were introduced, but other variables, particularly a decline in the number of farms, predict common milkweed trends more strongly over the period studied here.

The authors claim no conflict of interest, and do not identify a primary cause for the decline. But if they are correct, the situation is complex, and may require much more intelligent design by ecologists to figure out how best to preserve these icons of ID.

Photo: An aerial view of fairy circles in Western Australia, by Stephan Getzin/University of Göttingen, via EurkeAlert!