Intelligent Design

Intelligent Design

Making Predictions Against Design

From back when I was a sophomore taking biochemistry, one particular event stands out in my memory, perhaps because it was such an odd thing. Our professor, I’ll call him Dr. X, knew his material very well. Our classroom had nine blackboards stacked in groups of three. As he wrote on one, Professor X would flip a switch and blackboard A would advance upward, then B, then C, following some pattern that only he knew, until at the end of class, having dragged us all through metabolism, he would neatly draw an arrow connecting blackboard I’s reaction with the one on the starting blackboard. He always left me staring at my notes in despair of connecting them.

But that’s not what I remember about him the best. One day we were having a discussion about the marvelous things that were being found in biology. It was only a decade since the genetic code had been cracked, and the first DNA and the first protein had been sequenced. These were remarkable achievements. The development of the tools that made genetic engineering possible was happening there and then, at MIT at the time. I didn’t really realize how momentous it all was.

One thing Dr. X said stuck in my brain. He said, “We will find marvelous things in biology because nature is very inventive. But one thing we will never find is a wheel.” Maybe he thought that the wheel was a manmade machine, smooth, round, and designed. Biology was made of bumpy, lumpy proteins and was most emphatically not designed. But I speculate. He never gave his reasoning

Let us a have a moment of silence for such hubris, overturned so neatly by reality. Let me count the ways “unintelligent” nature has made circles, rotors, wheels, and gears:

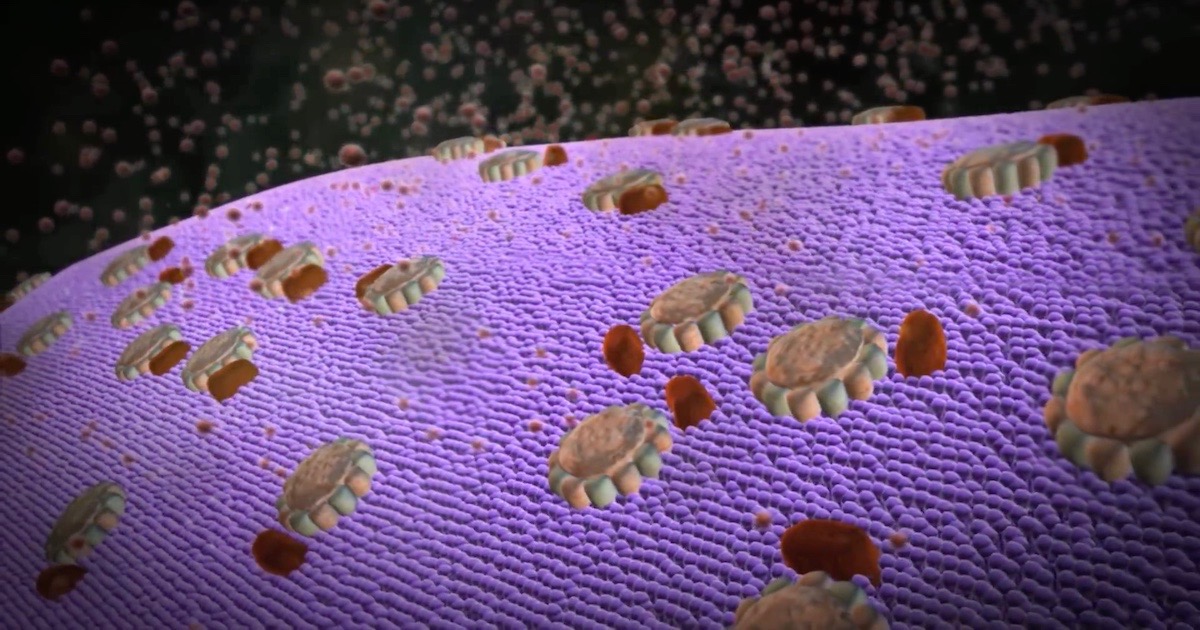

Porins

These proteins are pores in the membrane, holes to let compounds into or out of the cell. Not quite a wheel, they would be an uneven ride. The protein is shown here in three different ways: one showing every chemical bond (stick), one showing a cartoon of the protein’s secondary structure (the way the amino acids associate with one another), and one showing what the surface of the protein would look like to another protein, or a molecule trying to squeeze through its hole. Bacteria and mitochondria both have porins but not apparently of common origin.

Image source: Douglas Axe and Ann Gauger.

These molecules don’t act as true wheels. They don’t spin around an axle for transportation. But they move things through them and accomplish change that way, which it seems is greater than what Professor X imagined.

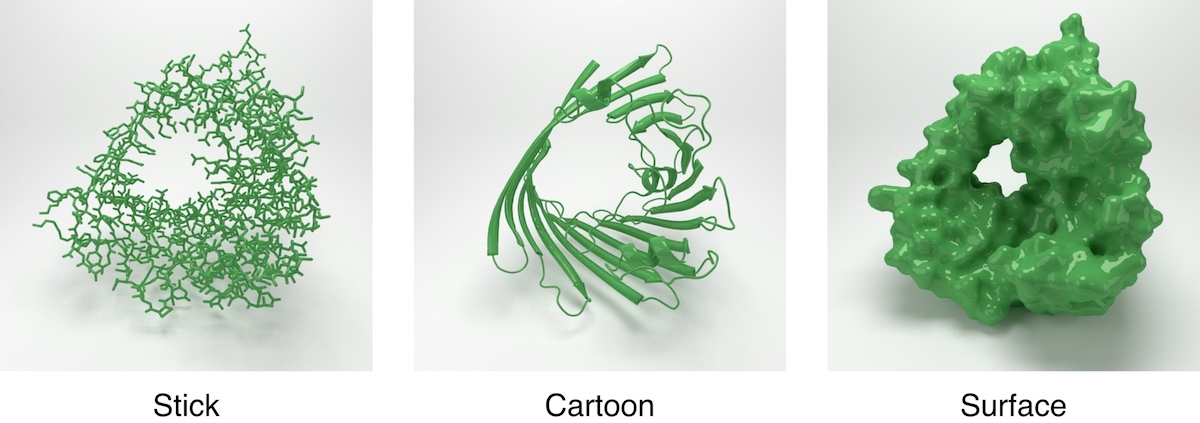

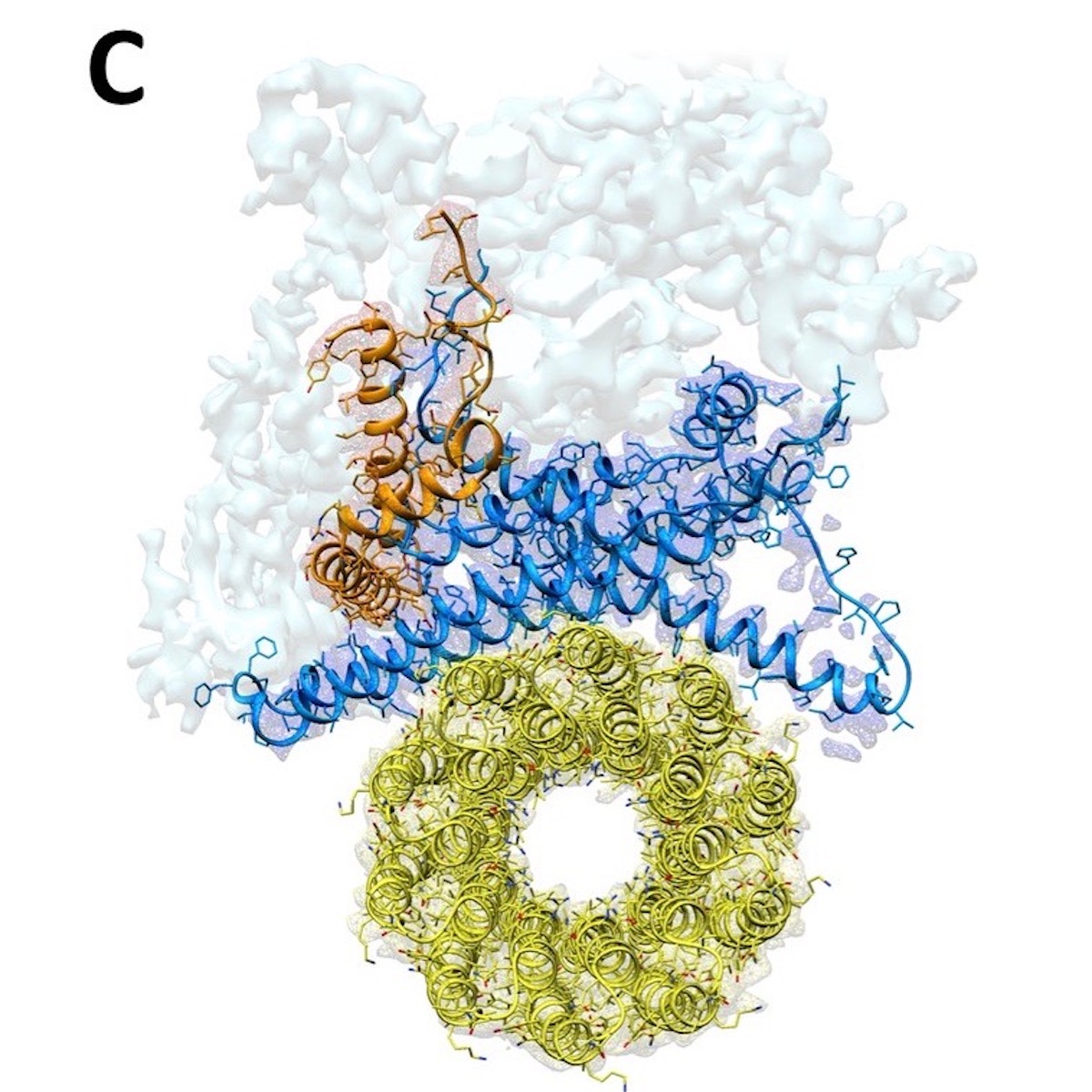

ATP Synthase

This molecular machine is 98 percent efficient at using a flow of protons across the inner mitochondrial membrane to change ADP back to ATP. Part of its essential inner structure is the c-ring rotor, shown in yellow. (For a general description of the whole process see this Discovery Institute video, “ATP Synthase: The Power Plant of the Cell.”) The technical paper describing the structure, and from which this figure is borrowed is here.

Image source: eLife, Creative Commons Attribution license.

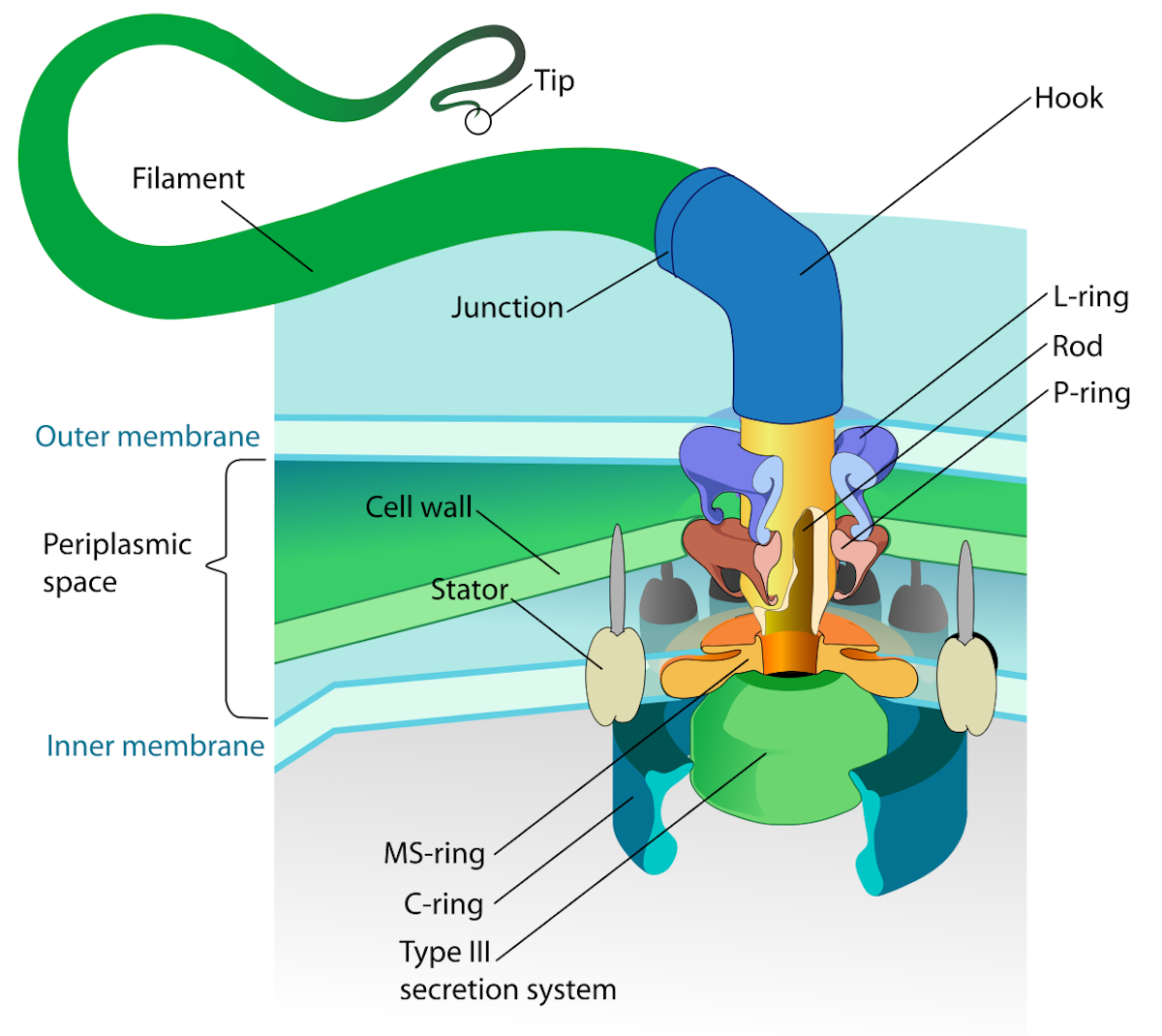

Flagellum

Not just a wheel, but a water-cooled, acid-fueled, rotary motor, capable of up to 17,000 rpm that can reverse directions in one quarter turn. Very much analogous to human motors, it has parts that function as a drive shaft, stator, bushings, gaskets, and the motor itself.

Image source: LadyofHats [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.

Diatoms

Well, maybe he didn’t mean whole organisms. But anyway:

Image source: Frank Fox [CC BY-SA 3.0 de], via Wikimedia Commons.

Leafhopper’s Gears

My professor didn’t mention gears, which are even more stupendous. But see for yourself:

- “Mechanical Gears Discovered on Planthopper Insects Provide an Opportunity to Recognize, or Deny, Design”

- “Insect Gears!”

Truthfully, no one in the early 1970s had any idea of the wonders there were still to discover in biology. And I think it’s safe to say, no one now should think we are ready to declare the riddle of life solved. We can’t even say that we are close to solving it, because we don’t know how much more there is to learn. Let’s let biology show us her wonders. Hubris has a bad name for a reason.

Image at the top: A scene from “ATP Synthase: The Power Plant of the Cell,” via Discovery Institute.