Faith & Science

Faith & Science

Theistic Evolution: The Case of Theodore Munger

So-called “theistic evolutionists,” including Kenneth Miller, Karl Giberson, and the BioLogos crowd, seem to think they can take Darwinian evolution and insert all sorts of theistic propositions into it unamended. That’s interesting for a theory explicitly aimed at excluding theology. But such oxymoronic thinking is the hallmark of Darwinian theism. It has created all sorts of confusions, such as making Darwinism a synecdoche for science, and worse, falsely imputing ideas to people who never held them.

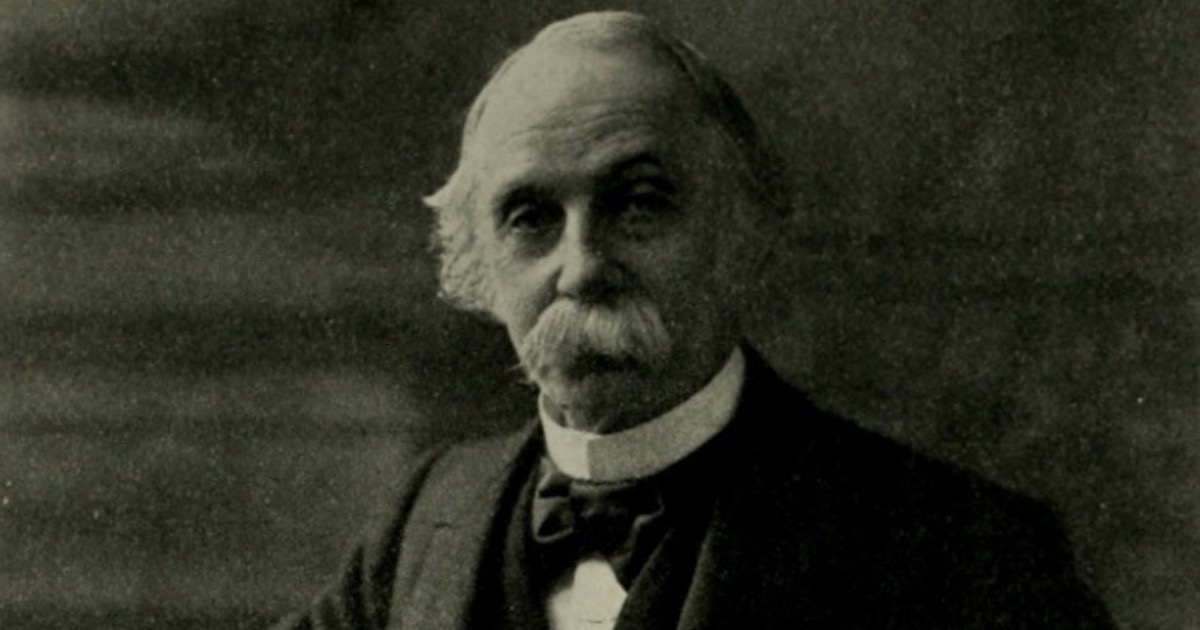

A case in point is the important 19th- and early 20th-century American theologian Theodore Munger (1830-1910). Munger, a leading voice for the “New Theology” that would increasingly make itself felt in America following the Civil War, had the qualities of piety and progressivism that allowed him to reconcile evolution with science and religion. Unfortunately, an opinion prevails that Munger’s lasting legacy resides in his promotion of Darwinian evolution. According to the scope notes of his papers residing at Yale, Munger “is remembered for his attempts to accommodate Christianity to Darwin’s theory of evolution.” But, in fact, nothing could be further from the truth.

“Evolution and the Faith”

In the May 1886 issue of The Century Magazine, in an extensive article of more than 10,000 words, Munger tackled the problem of “Evolution and the Faith.” He puts the reader on early notice that his brand of evolution is “very different from the evolution propounded twenty years ago.” Furthermore, acceptance of evolution need not entail common assumptions and inferences frequently associated with it. Munger proceeds to make six significant propositions regarding evolution:

- A properly construed and inherently teleological theory of evolutionary development provides a unified theory of organic development that places God in the center of creation. The laws of nature reveal an intelligent mover actively guiding them in a coordinated fashion towards a goal or purpose.

- In contrast to Darwin, Munger observes that our moral faculties’ relationship to our organic bodies in no way degrades or invalidates the divine nature of the human intellect. Mind and body “are united by the secret cord of the creative energy.” Although scientistic reductionists believe that it is brought about by natural forces, Munger argues that intelligence itself can only be brought about by an intelligent force working freely and progressively, and therefore possibly by increments.

- Of the rudimentary constituents of higher mental attributes in beasts, “There is only an indication that the moral is in the mind and purpose of God, even so far back as in the brute world — a foregleam of the approaching issue. They show the divine purpose . . . pressing on with yearning speed towards his [God’s] moral image.”

- Munger bemoans the positivism and scientism that has taken unwarranted ownership over evolutionary theory, and here is where the danger to the faith is realized.

- Munger further rejects Darwinian reductionism and positivism because it abandons the very reason upon which it is based and “attempts to measure the universe by a rod no longer than the eye can see.”

- Munger insists that four foundations must support every evolutionary proposition: a) every observed effect must assume a cause; b) a force cannot originate itself; c) a law must assume the priority of a mind; and d) forces working in a complex and orderly way toward a goal presuppose a mind or mind-like action behind them.

No Threat to Christianity

In the end, Munger’s purpose in this essay it to show that evolution not only poses no threat to Christian faith but can confirm it by linking God’s creative powers and purposes to the organic operations of nature.

Positivism, and Munger’s hostility to it, is extremely important when considering Darwinism. It was not necessary to insist upon Darwin’s principle of natura non facit saltum (nature does not make jumps) or even natural selection in order to be a Darwinist; what was crucial was some commitment to positivism. Munger’s essay challenges all aspects of positivism and proposes a new and distinctly different version of evolution that is intrinsically theistic.

Quickly Challenged

As might be expected, this view was quickly challenged. In the September 1886 issue of The Century, the Rev. Charles F. Deems, a Methodist minister from New York, accused Munger of conflating terms and providing a description of evolution contrary to most of its leading proponents. Where Munger used “evolution,” Deems insisted that he should have used “development” to avoid confusion. In fact, Deems points out that every time Munger holds fast to “the faith,” he is required to abandon evolution. But Munger tells his colleague, “I do not consider it wise to yield the word to the school that first brought it into general use and put its own definition upon it. It is not a trade-mark; it is not private property; and I must so far disagree with my friend as to think that it has not been so exclusively used by one school, that it cannot properly be used by other schools.”

But Deems had a point. If terms are used with such imprecision and multiple meanings, confusion is bound to arise. Nevertheless, Munger had every right to use the idea of organic change in nature as he saw fit. Darwin, Huxley, Haeckel and their allies did not own an exclusive trade-mark even if they acted as if they did.

Munger is exemplary of theistic evolution not Darwinian theism. In this sense he is closer to his contemporaries Alfred Russel Wallace and St. George Mivart, both of whom argued for intelligent evolution. So the next time you hear talk of theistic evolution, be sure to dig a little deeper. Darwinian theism — e.g., as espoused by Miller, Giberson, BioLogos — and theistic evolution are a confusion of terms. They are often not the same. Munger proves it.

In a post on Sunday I’ll give an example of how this same erroneous attribution is committed against a well-known American scientist. Stay tuned.