Physics, Earth & Space

Physics, Earth & Space

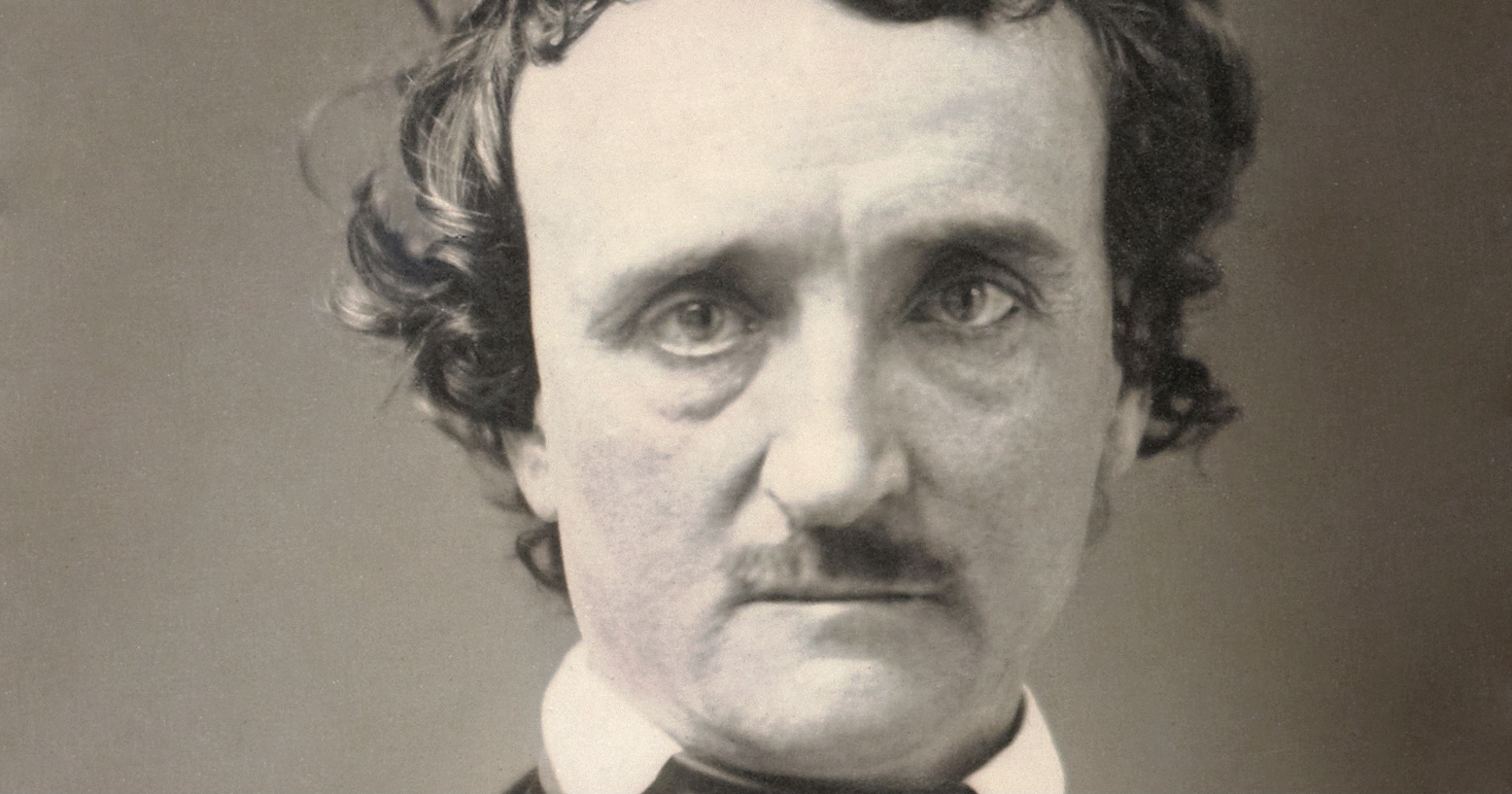

Edgar Allan Poe — Scientist

In order to think scientifically, you must have an advanced degree in science. And in order to think scientifically about a particular sub-discipline in the sciences, you must have an advanced degree in that particular scientific sub-discipline. Right?

Well, no, not necessarily. This may be the accepted “scientific” wisdom, but it’s based on a rigid view of what “the scientific method” actually involves. Some scientific problems are more like some mathematical problems: All that is needed to find the “Eureka” insight is the ability to tilt your head and look at a problem in just the right way. In my time as a math PhD student, I especially enjoyed the kinds of problems that required little or no theoretical build-up, because they allowed naturally astute people to show off their chops whether or not they had an alphabet soup after their names. It can be the same way in science.

Olbers’s Paradox

Stephen Meyer gives a lovely example of this in his new book Return of the God Hypothesis. The hero is neither a biologist, nor a chemist, nor a physicist, but the poet Edgar Allan Poe. The problem at hand was an astronomical puzzle known as Olbers’s Paradox, which got its name 250 years after philosophers and scientists had first begun trying to solve it. Here is the problem: Suppose (as most educated people did at that time) that the universe is infinitely large with a roughly uniform distribution of stars or star clusters. But if that’s true, then every line of sight should end in a star, just as every line of sight would end in a tree if you were standing in an infinite forest. So why is the sky dark at night? An easy question. A hard problem.

Maybe, some suggested, there’s a finite number of stars. Or maybe the all-explaining “ether” mopped up some of the light before it got to us. Maybe the light just ran out of steam.

“I Got There First”

Poe offered his solution in 1848, in an essay fittingly titled “Eureka: A Prose Poem”: The light of the most far-flung stars hasn’t yet had time to reach us. But such a statement only makes sense if the universe has a beginning. Thus, Poe reasoned, we have a finite universe, not yet old enough for the light from every star to have made the trek to Earth. This, he proposed, was “the only mode…in which…we could comprehend the voids which our telescopes find in innumerable directions.”

Poe would not live to see the field of astronomy catch up with his eureka flash. But in hindsight, we can posthumously award him the “I got there first” prize. With no formal training in astronomy or physics, Poe nonetheless had all he needed to claim it: a bit of ingenuity, a bit of imagination, a quiet moment to suck on his pen and daydream. Sometimes, that’s all you need. In that sense, what’s true for cooking in the world of Ratatouille can be true for science in our world: Anyone can do it.