Culture & Ethics

Culture & Ethics

Faith & Science

Faith & Science

Pressure, Propaganda, and Persecution through Mimesis

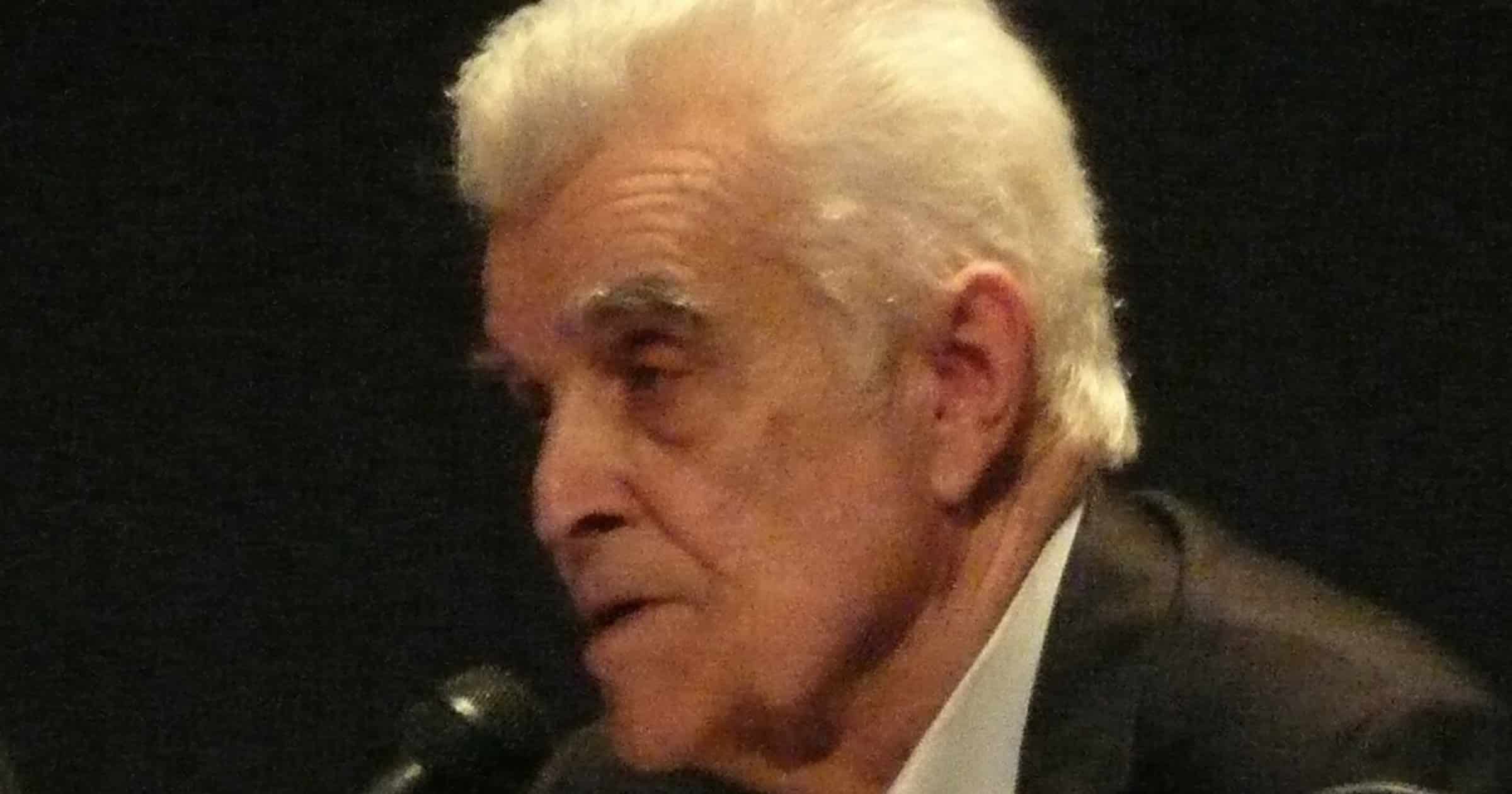

French philosopher René Girard discovered something new, new but very old, about human behavior — a model for human behavior that he saw operating in society at a very deep level, in large social groups as well as small ones. He called this behavior mimesis. Most people live mimetic lives patterned on what they see around them. They want what others want (thin desires) and never try to identify what their own deep desires (thick desires) might be.

Unfortunately, thin desires do not have the power to lead to a full integration of the human person. Such people are continually trying to “keep up with the Joneses,” so they want more of the things that signal wealth, power, and status. They become envious of those who have a better car, the latest sound system, the biggest house, or the most lavish vacation. It can advance to the state of covetousness. It can lead to bitterness, even hatred of those who have what they do not.

Thin desires come from comparing ourselves to others. It is made worse by social media, on places like Facebook, X (formerly Twitter), TikTok, and Instagram. Posts typically show only the best parts of people’s lives. Posts can also be used as a soapbox to promote their agendas. Such behavior when coordinated en masse can function as propaganda to produce mimetic behavior.

News channels are mimetic also. They deliver the news, but often they drive their viewers toward the editors’ political or social views. Broadcast media have done this for years, but now online sources drive viewers toward their points of view. Even movies and TV trigger mimesis. Essentially, any form of mass communication with a widespread audience can be called propaganda and cause mimetic behavior.

Let’s Pause Now and Consider

This idea is not new. “Enter through the narrow gate; for the gate is wide and the road is easy that leads to destruction, and there are many who take it.” The narrow gate that leads to salvation is the path of anti-mimesis or thick desires in Girard’s terminology. Those who choose the narrow way will find themselves at odds with modern culture. Those that follow the wide way that leads to destruction are those who follow the path of mimesis. They let worldly desires lead them. Let us take this to heart.

In terms of ideas, how is anything new or different ever to find an audience? The answer in our society is to commodify the idea or innovation and sell it to a large corporation with the means to produce or communicate the idea or innovation widely. Unfortunately, anyone with a radical new idea can either be ignored, or be labeled as crazy, or a heretic. Such innovators may be attacked if people feel threatened by this new way of thinking, and thus become scapegoats. Jews and Christians know all about scapegoats, or they should. On the Day of Atonement for the Israelites the ritual is described in Leviticus 16. Here is the part about scapegoats:

Then Aaron shall lay both his hands on the head of the live goat, and confess over it all the iniquities of the people of Israel, and all their transgressions, all their sins, putting them on the head of the goat, and sending it away into the wilderness by means of someone designated for the task.The goat shall bear on itself all their iniquities to a barren region; and the goat shall be set free in the wilderness.

For Christians, this ritual foreshadows the bearing of our sins by Christ. He takes them away. He atones. Girard recognized this parallel. Christ is the scapegoat, the victim set aside by God to bear our sins, but he is without sin himself.

That is not true in Girard’s earlier examples of the scapegoat, but it is accepted now that the scapegoat is an innocent victim. We have all seen this in operation. The suppression of whistleblowers of all kinds is a common thing that is amplified by the propaganda of the media. Those that reveal government secrets may face arrest and trial, and in some countries, execution. At the least their careers are ruined, and all social capital is lost. They will be shunned by colleagues and former friends because those people fear being tainted by association. Corporate whistleblowers may face similar fates. People who report sexual abuse, assault, or harassment must run a gauntlet of interrogations, disbelief, negative social commentary, and harassment in both printed and online form, and then they must testify about the nature of what occurred, often in public. Unfortunately, this persecution can be lifelong. Is it a surprise that many don’t come forward?

Suppression of new ideas can occur in any endeavor that depends on keeping up with the latest developments, collaborating with colleagues, or competing with rivals and holding onto status or power, or even a manager’s desire to avoid the difficulties of change. In other words, this form of suppression can occur in industry, technology, the military, medicine, religion, education, and science. Sadly, as a result these organizations may fail to promote important new ideas or prevent innovation. Also, rather than embracing the thick desires of people and their innovations, and letting individuals follow through on their ideas, those in charge may suppress them, using propaganda and coercion to do so.

How Much Do We Lose as a Result?

For example, leaders often reject innovations because of their resistance to change. Fixed ideas can be hard to overturn. “Everyone does it this way,” “It’s not possible,” “It won’t do any good,” or worse, “This idea is heretical and will overturn the existing way of thinking” may be their reactions and will stop positive change in its tracks. Every one of the organizations I mentioned above can treat innovators badly and destroy creativity and innovation. And if the elite think that a particular idea threatens their power and prestige, they may use widespread propaganda and persecution to suppress the new ideas.

I have seen all these behaviors in the scientific community, which is my area of expertise. More on that tomorrow.