Evolution

Evolution

Faith & Science

Faith & Science

What Really Happened at the Huxley-Wilberforce Debate?

Editor’s note: We are delighted to present an excerpt from the new book by Dr. Shedinger, Darwin’s Bluff: The Mystery of the Book Darwin Never Finished. This article is adapted from Chapter 5.

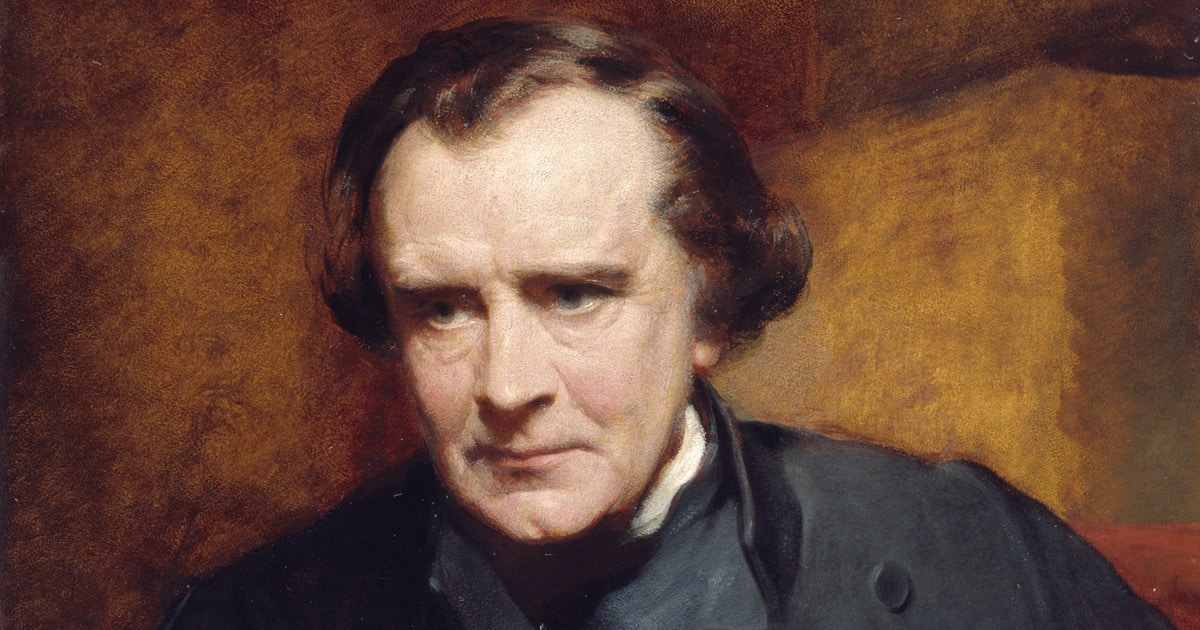

One of the better-known aspects of the Darwinian narrative concerns a debate over Darwin’s theory between Thomas Henry Huxley and Bishop Samuel Wilberforce at the British Association meeting at Oxford on June 30, 1860. Wilberforce is supposed to have asked Huxley if it was through his grandfather on his mother’s side or his father’s side that he was descended from an ape. Huxley is said to have replied that he would rather have an ape for a grandfather than a pompous member of the church establishment who injects ridicule into a serious scientific discussion, at which point women fainted. The received version of this event presents Huxley as the serious scientist and man of reason who won the debate over the unreasoning bishop who was unable to accept evidence when it flew in the face of church doctrine. The reality is more nuanced, however.

Darwin did not attend the British Association meeting due (of course) to health problems. But Hooker did and reported to Darwin on July 2 that a furious debate had ensued between Huxley and the anatomist Richard Owen the day before Hooker arrived, a debate that rendered Darwin’s book the topic of conversation at the meeting. He then continued:

Well Sam Oxon got up & spouted for half an hour with inimitable spirit uglyness & emptyness & unfairness, I saw he was coached up by Owen & knew nothing & he said not a syllable but what was in the Reviews — he ridiculed you badly & Huxley savagely — Huxley answered admirably & turned the tables, but he could not throw his voice over so large an assembly, nor command the audience; & he did not allude to Sam’s weak points nor put the matter in a form or way that carried the audience. The battle waxed hot. Lady Brewster fainted, the excitement increased as others spoke—my blood boiled, I felt myself a dastard; now I saw my advantage—I swore to myself I would smite that Amalekite Sam hip & thigh if my heart jumped out of my mouth & I handed my name up to the President (Henslow) as ready to throw down the gauntlet.

Hooker then tells Darwin that he verbally smashed Wilberforce, prompting rounds of applause. Unfortunately, the letter breaks off at this point. But on Hooker’s accounting, it appears it was he, not Huxley, who turned the tables on Wilberforce. Perhaps the version that places Huxley in the spotlight is merely the received wisdom consistent with Huxley’s later reputation as Darwin’s bulldog. On the other hand, Hooker was famously averse to public speaking, the principal reason he could never take up a teaching position, so perhaps Hooker embellished his own role at the meeting.

Darwin wrote back to Hooker the same day:

How I shd. have liked to have wandered about Oxford with you, if I had been well enough; & how still more I shd. have liked to have heard you triumphing over the Bishop. — I am astounded at your success & audacity. It is something unintelligible to me how anyone can argue in public like orators do. I had no idea you had this power. I have read lately so many hostile reviews, that I was beginning to think that I was wholly in wrong & that Owen was right when he said whole subject would be forgotten in ten years; but now that I hear that you & Huxley will fight publicly (which I’m sure I never could do) I fully believe that our cause in the long run will prevail. I am glad I was not in Oxford, for I shd. have been overwhelmed, with my stomach in its present state.

The next day Darwin wrote to Gray in a similar vein, informing him about the goings on at the British Association meeting and confidently asserting, “Owen will not prove right, when he said that the whole subject would be forgotten in 10 years.”

Lost to History

What exactly happened at the British Association meeting may be lost to history. The reports that have survived simply don’t match up. A third take on the meeting, appearing in the Athenaeum, paints a staider portrait:

The BISHOP OF OXFORD stated that the Darwinian theory, when tried by the principles of inductive science, broke down. The facts brought forward did not merit the theory. The permanence of specific forms was a fact confirmed by all observation…. He was glad to know that the greatest names in all of science were opposed to this theory, which he believed to be opposed to the interests of science and humanity.1

As for “Darwin’s bulldog,” as he later came to be called:

Prof. HUXLEY defended Mr. Darwin’s theory from the charge of its being merely an hypothesis. He said, it was an explanation of phenomena in Natural History, as the undulating theory was of the phenomena of light. No one objected to that theory because an undulation of light had never been arrested and measured…. Without asserting that every part of the theory had been confirmed, he maintained that it was the best explanation of the origin of species which had yet been offered.2

From these notes it does not sound like Huxley launched the kind of full-throated ridicule of Wilberforce that the received wisdom says he did, though, as will be shown presently, evidence exists to suggest that the Athenaeum may have intentionally left this part out.

An Overlooked Report

In 2017, Richard England brought to light an overlooked report on the British Association meeting published in the Oxford Chronicle that appears to be based on the same source as the Athenaeum report but with important differences. The Oxford Chronicle does in fact cite the famous exchange between Huxley and Wilberforce, a point that seems to be corroborated by other contemporary sources that recall the exchange. Thus, England concludes that the Athenaeum left the Huxley-Wilberforce exchange out in order to “prune controversial and indecorous material.”3 At the same time, England notes that the Oxford Chronicle was a liberal publication often critical of Wilberforce.4

But What About Hooker?

Both versions support the idea that Hooker made a statement meant to ridicule Bishop Wilberforce. According to the notes, Hooker charged Wilberforce with not understanding Darwin’s theory. Darwin never envisioned the transmutation of existing species into new ones. He merely envisioned the successive development of species by variation and natural selection. Hooker further rejected the idea that he accepted Darwin’s view as though it was a creed, for creeds have no place in science. Hooker had simply begun his work in natural history under the assumption that species were original creations, but now understood this to be just a hypothesis, “which in the abstract was neither more nor less entitled to acceptance than Mr. Darwin’s.”5

Whether it was Huxley or Hooker or both who ridiculed Wilberforce, the received narrative portrays Wilberforce as a bit of a buffoon, lacking the seriousness and knowledge necessary to criticize Darwin’s theory. John Bowlby terms him “an able man who knew nothing of science”6 while William Irvine says of Huxley, “It was well known that he had devoured alive the worthy Bishop of Oxford almost before the eyes of his congregation, leaving nothing but a shovel hat and a pair of gaiters visible on the platform.”7

The reality appears quite different. Hooker’s charge that Wilberforce misunderstood Darwin’s theory runs counter to the nearly 14,000-word review of the Origin Wilberforce published in the Quarterly Review, a review that documents how deeply Wilberforce understood Darwin’s work. Given Wilberforce’s status as a church official, we might expect his criticisms to have been based on theological objections. But Wilberforce appears to have anticipated this expectation and addressed it directly:

Our readers will not have failed to notice that we have objected to the views with which we have been dealing solely on scientific grounds. We have done so from our fixed conviction that it is thus that the truth or falsehood of such arguments should be tried. We have no sympathy with those who object to any facts or alleged facts in nature, or to any inference logically deduced from them, because they believe them to contradict what appears to them is taught by Revelation. We think that all such objections savour of a timidity which is really inconsistent with a firm and well-instructed faith.8

In contrast to the stereotypes that paint Wilberforce as a staunch defender of the absolute immutable nature of life forms, he makes clear that he is not averse to the doctrine of evolution by natural selection should the evidence weigh clearly in its favor. He even acknowledges not only that organisms vary, but also that natural selection has led to great diversity within specific types. Moreover, the struggle for life clearly exists, “and that it tends continually to lead the strong to exterminate the weak, we readily admit; and in this law we see a merciful provision against the deterioration, in a world apt to deteriorate, of the works of the Creator’s hands.”9 So natural selection for Wilberforce acts to maintain the fitness of species in their environment, thus preventing their deterioration.

Darwin Fails

But Wilberforce notes that what Darwin needs to show is that there is active in nature a power capable of accumulating favorable variations through successive generations toward the production of entirely new species. And on this point, according to Wilberforce, Darwin fails.

Commenting on the emphasis that Darwin places on pigeon breeding, Wilberforce argues, “With all the change wrought in appearance, with all the apparent variation in manners, there is not the faintest beginning of any such change in what that great comparative anatomist, Professor Owen, calls ‘the characteristics of the skeleton or other parts of the frame upon which specific differences are founded.”10 Likewise, humans have been breeding dogs for thousands of years, creating an enormous variety of breeds. But whether pigeons or dogs, artificial selection has never come close to creating a new species. Wilberforce then suggests that, given this, it is foolish to make an analogy between artificial selection and natural selection.

His scientific critique continues. “We think it difficult to find a theory fuller of assumptions; and of assumptions not grounded upon alleged facts in nature, but which are absolutely opposed to all the facts we have been able to observe.”11 In addition, the variations produced in domestic animals by breeders are selected because of their utility to people, not for the good of the animal. So artificial selection is simply irrelevant to what happens in nature. If natural selection is continually producing innumerable variations, where, Wilberforce asks, is the evidence for this in the geological record?

Wilberforce notes Darwin’s own concessions regarding the lack of geological evidence for his theory. Wilberforce writes, “This ‘Imperfection of the Geological Record,’ and the ‘Geological Succession,’ are the subjects of two laboured and ingenious chapters, in which he tries, as we think utterly in vain, to break down the unanswerable refutation which is given to his theory by the testimony of the rocks.”12 Wilberforce is unconvinced by Darwin’s argument that the geological refutation of his theory is only apparent, resulting from limited sampling, and the inherent imperfection, of the geological record. Darwin recognized the seeming sudden appearance of complex animals during the Cambrian era — a feature of the geological record known today as the Cambrian explosion — and openly admitted that if a long line of diversification in Precambrian deposits failed to show up in the fossil record, his theory would be in ruins.13 Wilberforce took this concession and ran with it. “Now it is proved to demonstration by Sir Roderick Murchison, and admitted by all geologists, that we possess these earlier formations, stretching over vast extents, perfectly unaltered, and exhibiting no signs of life.”14

Did the ensuing decades make a fool of Wilberforce? In fact, the findings of modern paleontology substantially agree with Wilberforce here. The wealth of Precambrian transitional fossils that Darwin hoped would be discovered and so rescue his theory have remained persistently absent, despite assiduous efforts to locate them, and despite the fossil record having shown itself quite capable of preserving other Precambrian fossils.15

Darwin’s Handling of Time

Wilberforce further objected to Darwin’s handling of time: “The other solvent which Mr. Darwin most freely and, we think, unphilosophically employs to get rid of difficulties, is his use of time. This he shortens or prolongs at will by the mere wave of his magician’s rod.”16 Wilberforce accuses Darwin of positing enormous stretches of time in places where his theory requires them, but then gathering up into a point the duration in which certain forms of life prevailed, thus obscuring the fact that, as the fossil record shows, many forms of life endured for many millions of years without undergoing substantial change.

Similarly, Wilberforce also objected to Darwin’s employment of facts: “Together with this large licence of assumption we notice in this book several instances of receiving as facts whatever seems to bear out the theory upon the slightest evidence, and rejecting summarily others, merely because they are fatal to it. We grieve to charge upon Mr. Darwin this freedom in handling facts, but truth extorts it from us.”17

The stereotype portraying Wilberforce as the pompous bishop rejecting Darwin on theological grounds is easily dispelled by the scientifically informed, scientifically focused, and comprehensive nature of his lengthy review. Hooker may have accused Wilberforce of not understanding Darwin’s theory, but Wilberforce’s review suggests he understood it only too well.

Notes

- Burkhardt, Correspondence, 8: 595.

- Burkhardt, Correspondence, 8: 595.

- Richard England, “Censoring Huxley and Wilberforce: A New Source for the Meeting that the Athenaeum ‘Wisely Softened Down,’” Notes and Records 71 (2017): 379.

- England, “Censoring Huxley,” 381.

- Burkhardt, Correspondence, 8: 596.

- John Bowlby, Charles Darwin: A New Life (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1990), 354.

- William Irvine, Apes, Angels, and Victorians: The Story of Darwin, Huxley, and Evolution (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1955), 272.

- Samuel Wilberforce, review of The Origin of Species, by Charles Darwin, Quarterly Review (1860): 256.

- Wilberforce, review of The Origin, 233.

- Wilberforce, review of The Origin, 237.

- Wilberforce, review of The Origin, 238.

- Wilberforce, review of The Origin, 240.

- In chapter 10 of the Origin, under the subtitle “On the Sudden Appearance of Groups of Allied Species in the Lowest Known Fossiliferous Strata,” Darwin wrote, “The case at present must remain inexplicable; and may be truly urged as a valid argument against the views here entertained.” Darwin, Origin, 254.

- Wilberforce, review of The Origin, 245.

- Precambrian deposits do show signs of primitive life. But the long gradual succession from these primitive forms up to the complex animals of the Cambrian Explosion continue to be absent from Precambrian deposits. See Douglas H. Erwin and James W. Valentine, The Cambrian Explosion: The Construction of Animal Biodiversity (Greenwood Village, CO: Roberts, 2013); Stephen C. Meyer, Darwin’s Doubt: The Explosive Origin of Animal Life and the Case for Intelligent Design (New York: HarperOne, 2013); and David Klinghoffer, ed., Debating Darwin’s Doubt: A Scientific Controversy that Can No Longer Be Denied (Seattle, WA: Discovery Institute Press, 2015).

- Wilberforce, review of The Origin, 250.

- Wilberforce, review of The Origin, 250.