Evolution

Evolution

Intelligent Design

Intelligent Design

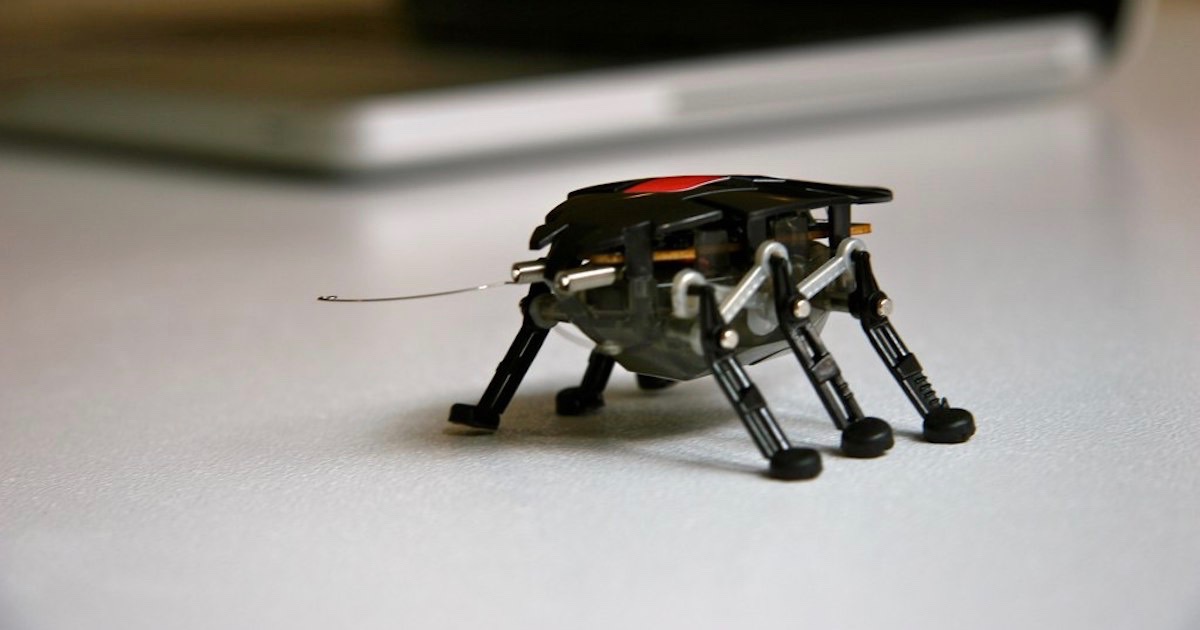

Digital Evolution and Bohemian Bugs

Most of us can relate to things going not quite as expected. Sometimes they go spectacularly or even hilariously wrong. All software engineers have been burnt by those sneaky “bugs” that manage to get past the defenses. It’s almost as if they just don’t care what’s expected of them. They totally ignore the status quo, and do their own thing, sometimes very surprising things. They totally “think outside the box.” A bug is, by definition, something that the intelligent designer didn’t think of. That makes it pretty smart, huh? It is almost like bugs are “creative,” like Bohemian artists who live on a shoestring in condemned buildings — all to demonstrate their radical freedom!

Evolution is a bit like that. Here is a new collection of anecdotes, “The Surprising Creativity of Digital Evolution,” that describes all the crazy ways digital evolution does unexpected things. It is pretty entertaining if you are into that kind of thing. It turns out evolving digital organisms are really, really good at finding glitches in their matrix. They are also good at following white rabbits.

Bugs and Glitches

The vast majority of the examples involve “bugs.” Some of these are creative interpretations of the problem assigned (like the student who is too “smart” to do any real work). There is the creature that “travels” further than its peers by being really tall and falling over, or “jumps” by having a high center of mass and kicking its legs away. There are many other examples that could be added to the list in the article. For instance Winston Ewert relates playing a simulated version of BattleBots, and instead of designing the strategy, he left evolution to do it unsupervised. It didn’t work out so well:

I wrote a genetic algorithm that evolved the strategy of a tank in a simulated 1v1 battle with another tank. After I ran it for a while, I watched the resulting battle. My tank proceeded to drive as fast as it could into the wall on the opposite side of the arena, and then repeatedly rammed itself into the wall until it died. Why? Evolution couldn’t find any way to effectively compete with the opposing tank, but it could deprive it of credit for the kill by committing suicide.

So we’re dead, but at least we didn’t lose! This is also how cancer works: Cells break free of their intelligently designed programming, end up competing with each other for space and resources according to natural selection, and in the end they are all dead.

A bunch more of the examples involve glitches in the matrix. Unlike in real life, conservation of energy is very finicky to enforce in a physics simulation. If you make a mistake, digital organisms will find it, and tap into it as a free source of energy. Some use this to ‘borrow’ energy for jumping (with no intention of paying it back). Some use it to climb walls. You name it. Others win at tic-tac-toe simply by specifying large coordinates that boggle the electronic mind of the opponent.

Hacks, Botches, and Dead Ends

To be fair, some of the examples are borderline non-bugs and arguably real solutions: In one case, a robot arm “figures out” how to open its disabled hand by ramming it. In another, a digital organism “creates” an “odometer” to stop exactly where the food stops without having to bother sensing it. In another case, the robot turns upside down to walk on its “elbows.” These are unexpected solutions, but notice they are extremely simple compared with the complexity they started with, and compared to the solution they were intended to achieve. Very simple solutions are sometimes within reach of evolution. One example is Lenski’s citrate-eating bacteria, where random mutations hacked the controls of an existing citrate transporter (an existing complex machine) to turn it on all the time instead of just some of the time. Mike Behe has written about it (and the hype) here. No one thinks you need ID for that kind of thing. ID is needed when you have not just a specification but complexity. Note that the disabled hand was not re-enabled. No new limbs were grown.

Also note that the odometer would be completely useless on another food trail; it is an evolutionary dead end. This is a common problem in the field of machine learning, where the algorithm learns the data rather than learning anything from the data. One can all too easily end up with an algorithm that perfectly memorizes the data it was trained with, but is totally stymied when faced with something new.

Another example I thought was pretty cool was the “Evolution of Muscles and Bones.” It doesn’t explain the origin of muscles and bones, but it does show how a simple inchworm “gait” can appear quite easily once you have them.

Creativity and Determinism

But why do evolutionists want to label this stuff as “creativity”?

It seems to me they are thinking of creativity as being closely connected to philosophical questions such as free will and determinism. This is a very common way to frame it within the ID camp as well. Thus they want to demonstrate how unpredictability or surprise or alternate possibilities or “freedom” can arise without any will at all, from random or pseudo-random, chaotic deterministic systems. They want to show that evolution can do things it was never designed or “framed” to do; things that appear not to be predetermined. And yes, of course it can. But there is much more to intelligence than that.

This is one reason I don’t like to frame intelligent design that way. Another reason is: If the main characteristic of ID is that it does unpredictable or surprising or non-deterministic things, then how can it predict anything? If it does not predict anything, then how can it become a scientific theory?

There are two major ways of thinking about free will. The one you are probably most familiar with is called libertarian free will. It claims that free will is all about not being determined. The other view, compatibilism, claims that free will is about not being coerced; you are free if you are able to do what you want to do, irrespective of whether the choice was ultimately determined. Some people don’t see any difference, or don’t think the distinction makes sense, but I have come to be a compatibilist.

Instead of thinking about how ID seems to infinitely expand the space of possibilities, I prefer to think about how intelligent design reduces an already infinite space of possibilities to just the interesting ones, thus predicting those possibilities. In the sense that intelligent creativity reduces possibilities, and is a kind of predictable causation, it is not only compatible with determinism; it is a certain kind of determinism. This is a compatibilist view of ID.

Instead of thinking of “creative” as mystery or surprise (like a Bohemian artist), maybe “creative” should be thought of as more like constructive: choosing functional complexity out of a vast space of chaotic possibility and then deliberately building what would be extremely unlikely by chance.

A lot of the bugs in the article are creative in the sense of being surprising, or non-predetermined, but none of the bugs are creative in this sense of doing complex constructive work.

White Rabbits

Beyond the bugs and hacks, there are some examples of digital evolution that do seem to be creative, in the sense that evolution seems to construct new functional solutions. Prime among these is the Avida digital ecosystem mentioned. These digital creatures appear genuinely able to create complex solutions much more quickly than chance alone would allow. None of these complex solutions are pre-programmed into the organisms, or into the environment. It seems like digital evolution is being genuinely creative.

However, that is a mirage. Bob Marks, Bill Dembksi and Winston Ewert have shown that the world of Avida is full of features that tend to guide evolution towards a specific and complex target (EQU), subgoal by subgoal. They call these features Active Information. You could think of each of these as being like the white rabbit in The Matrix. The white rabbit is a very ordinary feature of the universe, but it has been purposefully placed there or given meaning from outside, and you can tell by what it leads to; cumulatively these inconspicuous nudges lead Neo somewhere in particular. Avida works for the same kind of reason, and you can even measure it. For more in this vein, have a look here.

I don’t think the little creatures in Avida are conscious, but if they were, they ought to have a good hard think about why they are so brilliant.

Photo credit: Alberto D’Ottavi, via Flickr.