Evolution

Evolution

Meet the Fuxianhuiids: Exploding Cambrian Arthropods

Fuxianhuiids are extinct “true arthropods” of the early Cambrian, having appeared without evolutionary ancestors in the Cambrian explosion. If you dare, go ahead and try to pronounce the name, which comes from a lake in South China named Fuxian Hu. The group is briefly mentioned by Stephen Meyer in Darwin’s Doubt. These animals are about 4 cm long, and Current Biology offers a “Quick Guide” to them. First question: What are Fuxianhuiids?

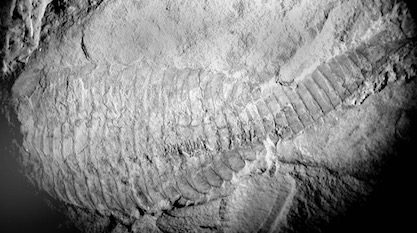

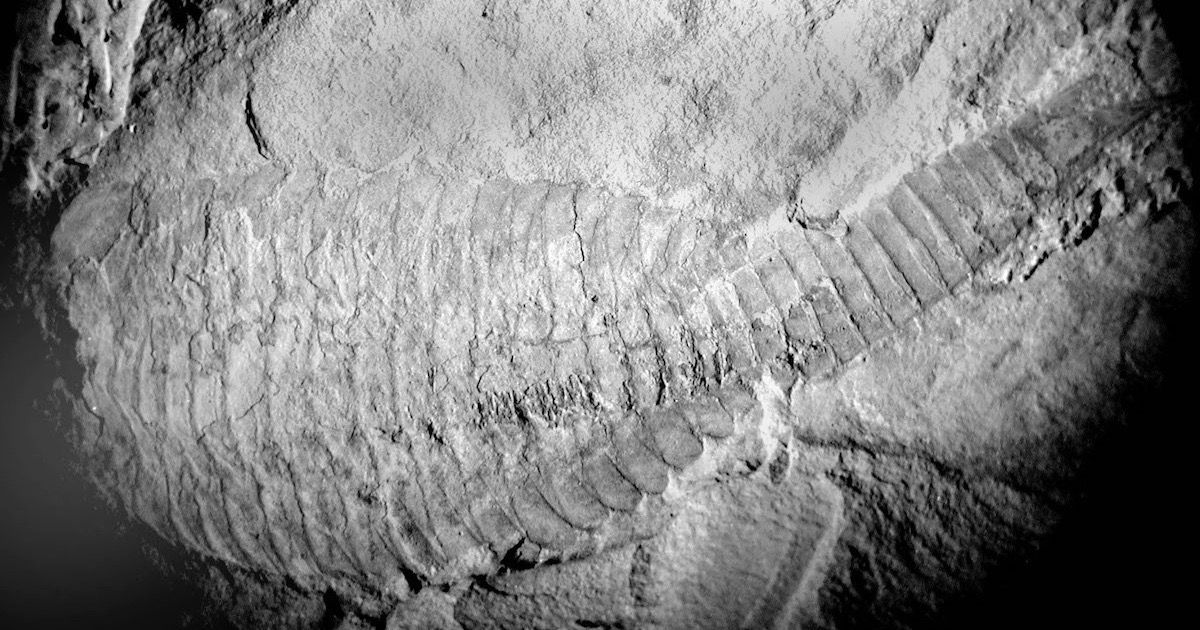

The fuxianhuiids — of which there are eight species described so far — are a clade of extinct soft-bodied euarthropods (colloquially: arthropods) that are known from early Cambrian marine deposits in South China (Figure 1). They are widely regarded as distant relatives of extant euarthropod groups — namely arachnids, myriapods, crustaceans and insects. The exceptional preservation of their fossils has provided unique information on their morphology (Figure 2). Fuxianhuiids have contributed towards a better understanding of the early evolutionary radiation of euarthropods — the most successful animal phylum in the history of life on Earth — and led to a detailed reconstruction of the origin of the euarthropod body plan. [Emphasis added.]

As expected, they say up front that these animals are helping evolutionists understand evolution better. It’s not surprising that fuxianhuiids are “widely regarded” as “distant relatives” of arthropods; that is expected Darwinian posturing. And yet fuxianhuiids are arthropods, the article admits. An arthropod body plan is no simple thing to explain in a sudden, explosive appearance.

The article goes on to say that all eight species of fuxianhuiids are found in South China. The earliest come from the Chengjiang biota dated at 520 million years ago (mya). Other euarthropods, such as trilobites, are found all over the globe. On page 60 in Darwin’s Doubt, Meyer lists five types of arthropods that appear suddenly in the Cambrian: trilobites, Marrella, Fuxianhua protensa, Waptia, and Anomalocaris. Some of these are well known from the Burgess Shale in Canada, dated later than the Chengjiang at 505 mya. Meyer cites Doug Erwin and others who place the main pulse of the explosion at 530 to 525 mya (6 million years), or at most 530 to 520 mya (10 million years). The earliest known fuxianhuiid thus appears at the end of the main pulse of the Cambrian explosion. They are nearly contemporaneous with the earliest trilobites, which are found at many locales simultaneously at 521 mya, according to this paper in PNAS. This implies the explosive appearance of at least two arthropod stem lineages, fuxinahuiids and trilobites, at close to the same time. Due to uncertainties in time resolution of fossils, they could well overlap.

Fuxianhuiid Complexity

The Quick Guide mentions these organs and features of fuxianhuiids:

- A body with 15 to 40 segments within a hardened exoskeleton

- A pair of stalked eyes

- Antennae

- A mouth with serrated mouthparts

- A tail with paired flukes making up a swimming paddle

- Dozens of branched walking legs, some ending in claws

- A nervous system with “complex tri-partite brains comparable to some extant crustaceans and insects”

- A circulatory system

- A gut with diverticulae, “which are regarded as physiological adaptations for aiding efficient digestion or storage pockets for infrequent feeding.”

These morphological features indicate complex behaviors: swimming, eating, sensing, and reproducing. They were “functional wholes” with muscles, brains, nervous systems, sensory organs, sex organs, digestive systems, circulatory systems, and everything needed to succeed in their environment. Undoubtedly they came programmed with behavioral responses to stress or predators, and with instincts to operate the complex organs they sported.

Evolutionary Considerations

The last question in the Quick Guide is, “What do they tell us about euarthropod evolution?”

Fuxianhuiids have helped reconstruct the phylogenetic relationships of Cambrian euarthropods, as well as the step-wise evolution of their body plan. As the stem-lineage includes segmented worm-like organisms (e.g. lobopodians, radiodontans) that lack several of the key characters commonly associated with extant groups, fuxianhuiids are among the earliest representatives that have archetypical euarthropod traits, such as the dorsal exoskeleton, jointed limbs with a feeding function and a multisegmented head. Because of their basal phylogenetic position, fuxianhuiids offer critical insights on the ancestral morphology of euarthropods before the major post-Cambrian diversification of crown-group chelicerates (e.g. arachnids) and mandibulates (e.g. myriapods, crustaceans, insects). For example, fuxianhuiids have illuminated the addition of anterior segments into a functional head, the evolution of euarthropod limbs with a feeding function and the diversity of body segmentation in Cambrian euarthropods.

Wait a minute; how can these creatures “illuminate” the addition of traits when they already had them? That’s like saying that a kitchen with indoor plumbing illustrates the evolution of indoor plumbing. Where is the sequence of ancestors from worm to arthropod? This presumed descendant of a “worm-like” lobopodian or radiodontan comes with multiple “archetypical euarthropod traits” working together: (1) a dorsal exoskeleton, (2) jointed limbs with a feeding function, and (3) a multi-segmented head. These things presuppose new cell types, new architecture, and new behaviors.

Lobopodians (“wolf-feet”) have stubby legs (e.g., tardigrades, Hallucigenia). Radiodontans (“circle-teeth”) are already classed as arthropods (e.g., Opabinia, Anomalocaris). Both clades are well represented in the Burgess Shale of more recent age. Fuxianhuiids cannot have evolved from their descendants. All three of these groups are contemporaries, not evolving into one another, and all three have complex organ systems and tissue types seen in fuxianhuiids. There’s neither a sequence in time or in complexity. We can find variation and diversification within each type after they appear, but not Darwin’s ancestor relationships.

Wikipedia is no help about this animal’s evolution, despite its strongly pro-Darwinian stance:

Fuxianhuia protensa is a Lower Cambrian fossil arthropod known from the Chengjiang fauna in China. Its purportedly primitive features have led to its playing a pivotal role in discussions about the euarthropod stem group. Nevertheless, despite being known from many specimens, disputes about its morphology, in particular its head appendages, have made it one of the most controversial of the Chengjiang taxa, and it has been discussed extensively in the context of the arthropod head problem.

And that problem, as you learn by clicking the link, is “a long-standing zoological dispute concerning the segmental composition of the heads of the various arthropod groups, and how they are evolutionarily related to each other.” Called “the endless dispute” as far back as 1975 because of “its seemingly intractable nature,” the arthropod head problem remains unsolved. Wikipedia says that “the precise nature of especially the labrum and the pre-oral region of arthropods remain highly controversial.”

The Arthropod Head Problem

Fuxianhuia is Exhibit A in the arthropod head problem. The authors of the Quick Guide include Javier Ortega-Hernández, who tried to solve it in 2015, as noted here. His solution was “less than convincing,” and he ignored the larger problem of the Cambrian explosion.

This Quick Guide guides people astray. The authors do a disservice to readers by implying that evolution is being “understood” better because of fuxianhuiids. They don’t even mention the Cambrian explosion or the arthropod head problem. The authors grin cheerfully about how fuxianhuiids are shedding light on evolution, but backstage they are cramming data into a pre-determined belief system instead of following the evidence where it leads. If an unbiased scientist dug up a fossil fuxianhuiid and held it in her hands, would she see a vision of Darwin?

Science should observe these complex animals on their merits. If there’s no clear trail of increasing complexity leading up to them, so be it. Don’t make one up.

Photo: Fuxianhuia protensa, by Grahbudd at English Wikipedia (Transferred from en.wikipedia to Commons.) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.