Evolution

Evolution

Louis Agassiz: Some Additional Thoughts

Robert F. Shedinger’s interesting post yesterday on Louis Agassiz brought to my mind some additional thoughts on this complex figure in the annals of American science. Shedinger is quite correct in highlighting Agassiz’s staunch opposition to Darwin and his creationist perspective. He is also correct in pointing out Agassiz’s tireless efforts at “working to bring American science up to the standards of Europe.” This, as he points out, includes his establishment of the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard as well as his role in founding the National Academy of Sciences. These are indisputably notable achievements.

Benighted Racial Views

Agassiz had his demons, however, and Shedinger cites my article, “Plato Meets Polygeny,” that discusses his rather benighted racial views (available open access in the Journal of the Southern Association for the History of Medicine and Science). In fact, those views make Agassiz a problematic figure in the complex intellectual terrain of mid-19th century Anglo-America. (Since this essay is readily obtainable, I’ll not belabor the details here.) But despite the significance of Agassiz’s scientific accomplishments, his heavy historical baggage cannot be lightly discarded or ignored.

First of all, his biblical exegesis of multiple Adams with its presumption of separate racial origins (and hierarchies) incurred the ire of the vast majority of the Christian community even in his own day, with only Southern sympathizers rushing to its defense more for political than religious reasons. Orthodoxy was quickly cast aside by apologists for the South’s “peculiar institution,” a dubious alliance at best for a man of science like Agassiz.

Not Far from Darwin

But second, and more importantly, Agassiz’s racial views were not, in the final analysis, that far from Darwin’s own. Like Darwin, Agassiz was convinced that craniometry was an accurate measure of racial difference and mental capacity. Darwin’s approving references to the craniometric data of Paul Broca and Joseph Barnard Davis were matched by Agassiz’s embrace of Samuel George Morton’s Crania Americana (1839) and Crania Ægyptiaca (1844). Despite Agassiz’s vocal opposition to Darwinian evolution, he ended up siding with Darwin on the race question. Thomas Henry Huxley largely echoed Darwin’s and Agassiz’s sentiments on race.

How could this be? It turns out Agassiz makes the same mistake Darwin did; he failed to make an all-important distinction between human and animal. Agassiz wrote, “the differences existing between races of men are of the same kind as the differences observed between the different families, genera, and species of monkeys or other animals; and that these different species of animals differ in the same degree one from the other as the races of men,” some even more so. Agassiz emphasized that this is “one of the most important and unexpected features in the Natural History of Mankind.” This is hardly different from Darwin’s own assertion in his Descent of Man (1871) that there is “no fundamental difference between man and the higher mammals in their mental faculties.” Whatever Agassiz’s “creationist” commitments, he (like Darwin) made a cardinal error: he rejected human exceptionalism, a foundational Judeo-Christian concept. In short, Agassiz practiced heterodox religion and bad science.

Praise for Richard Owen

If I had to praise a contemporary of both Agassiz and Darwin who did not share these untenable notions it would be Richard Owen, an opponent of Darwin who defended racial equality on scientific grounds and held to a structuralist formulation of nature fully compatible with purpose and human exceptionalism. Owen’s courageous defense of racial equality and Huxley’s disingenuous Darwinian racism is carefully examined in Christopher E. Cosans’s Owen’s Ape & Darwin’s Bulldog.

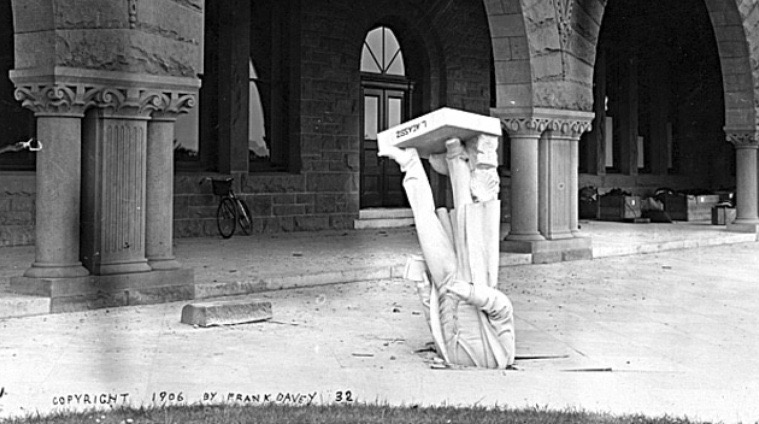

Whenever I think of Agassiz I can only recall his statue buried in the pavement in front of the Stanford zoology building following the San Francisco earthquake of 1906, a tragicomic reminder of a once famous scientist who ended up irrelevant even to a fellow Darwin doubter like American science polymath James Dwight Dana. As I conclude in my essay, “Agassiz became a lamentable figure lost in the murky shadows of his own Platonist forms.” And there he will likely remain.