Faith & Science

Faith & Science

Theistic Darwinism’s “Fully Gifted” Creation Theology Contradicts Itself, and Science

It’s easy to see modern evolutionary theory and Christianity as mutually exclusive. After all, evolutionary theory attributes the origin of all the species around us to a blind process fueled by accidental genetic mutations. Christianity teaches that a creative intelligence, God, created all this. Nevertheless, there are many sincere Christians who embrace some form of Darwinism and attempt to reconcile it with their Christian faith. They would say that Darwinism and faith in the God of the Bible are completely compatible.

Are they completely compatible? And are there good reasons for Christians to graft modern Darwinism onto their Christian worldview?

The “Fully Gifted” View

Many Christian evolutionists argue that a Darwinian evolutionary model is actually theologically superior to the traditional idea of God working directly to create various plant and animal forms. The argument goes like this: Our all-wise, all-powerful God could and would have rigged the beginning of the universe so cleverly that he wouldn’t need to intervene later to create life. Instead, it would all simply unfold from that first cosmic seed. Only when God was ready to exalt one of the ape-like species by investing it with an immortal soul did he need to intervene. In between he could just let his wonderful universe do its evolutionary thing.

On this view, there appears to be a good theological reason to expect only unbroken material causes when studying nature. This view appears to be rooted in two tenets of orthodox Christian doctrine — God’s omnipotence and his unsurpassed wisdom. Howard van Till calls this evolutionary view of creation “fully gifted creation.”1 It’s a creation that doesn’t need follow-up tinkering to generate life because, well, the creation is “fully gifted.”

Notice that the phrase “fully gifted creation” implies that the more traditional view of God’s creative activity in Genesis involves a deficiently gifted creation. There are two problems with van Till’s understanding: (1) the theological reasoning breaks down when pressed, and (2) the scientific evidence points in a different direction.

A Crucial Inconsistency

First, notice that this “fully gifted creation” has a lot in common with the old “watchmaker” view of the creator: God as the master craftsman who created the perfect cosmic mechanism and so has been able to just let it run without additional tinkering. This is modern deism, not Christian theism. In the latter, the Maker of heaven and earth doesn’t want to wind up the world and leave it be. He wants to stay personally involved with his creation. He wants to get his hands dirty. His relationship to his creation is more like that of a gardener to his garden, a loving father to his children, or a lover to his beloved.

The watchmaker metaphor helpfully reminds us of the many mathematical regularities of God’s world. But as with all theological metaphors, we need to remember its limitations and employ additional metaphors that reveal other aspects of God’s relationship to his creation.

Some who advocate “a fully gifted creation” would object that they see God not as a distant designer but as one “in whom we live and move and have our being,”2 a divinity immanent but never tinkering. This formulation also runs into difficulties. It assumes that a God who is simply immanent is superior to a God who is immanent but also active in ways not reducible to mathematical regularities. This is hardly obvious.

The formulation also fails to remedy a crucial inconsistency. The “fully gifted” argument makes use of an important tenet of traditional Christian theism in one part of its argument, but rejects that same tenet in another part.

According to orthodox Christian theism, God invented and transcends the time in which we exist — past, present, and future. The idea of God transcending our space-time continuum is a mind-boggling one, but it’s biblical. In Psalm 90, Moses says that to God a day is like a thousand years and a thousand years is like a day. God also describes himself as the I Am. He somehow knows about and predicts events hundreds of years in the future. In the book of Revelation, God the Son calls himself the Alpha and the Omega, the beginning and the end. And in John’s Gospel, Jesus uses a surprising verb tense when he tells his listeners, “Before Abraham was born, I Am!”

We can use the idea of God being over and above the time of this universe to help us begin to grasp how he could exist before the space and time of our universe came into being in the Big Bang. So far, so good. Many theistic evolutionists also use this idea to explain how God could know that his finely tuned new universe would one day evolve to generate our Sun, planet Earth, the first living things, and, eventually, a species suitable for an immortal soul made in the image of God. If God is outside of time and all-knowing, he can see the past, present, and future of every possible universe he might create, all in a single heavenly glance.

Again, so far, so good. But now here’s a problem: If we agree that God stands over and above time past, present, and future, why criticize the design theorists who argue that the maker of the universe appears to have done some of his design work between the origin of the universe and the origin of humans? If God stands over past, present, and future, there is a sense in which all of his design work occurred in the eternal present of the “I Am,” whether that work occurred “all at once” 14 billion years ago or at different points throughout the history of the universe. Theistic evolutionists treat God as time-bound when it suits their argument, and beyond time when it suits their argument. That’s faulty reasoning all the time.

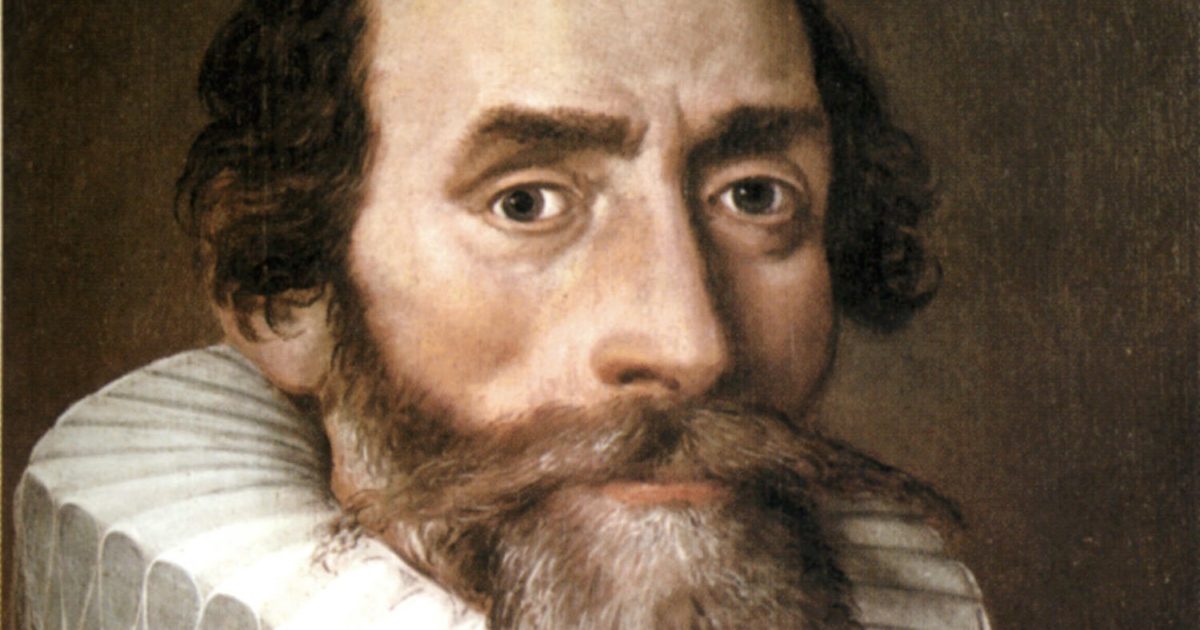

Kepler’s Approach

Now on to the second problem. Humility cautions us against placing too much confidence in our judgments about how God would have done things. In previous centuries, many people were convinced that a perfect God would construct our solar system so that the planets revolved in perfectly circular orbits. It turned out that they follow an elliptical path instead — nearly circular but not quite. Johannes Kepler (1571–1630) hit upon this truth in part because he was willing to entertain the possibility that he couldn’t determine deductively how an all-wise and all-powerful God would construct the solar system. He had to study nature, to listen with great care to what it might tell him, and from that try to discover how a free and powerful God actually did it.

Kepler’s approach is representative. One way in which Christian theology helped to give birth to the scientific revolution was by insisting that God was free to create however he wished, within the guidelines of his own good and reasonable nature. This meant that scientists would need to carefully test their ideas about how God had designed some particular feature of nature to see if they had guessed correctly. They couldn’t just work the problem out deductively. This encouraged observation and testing.

The Question of Progressive Creation

Some theistic evolutionists insist that the Creator would not act progressively in the history of Creation, and moreover, that he wouldn’t leave behind powerful physical evidence of his designing work, lest it leave no room for a leap of faith. Such a judgment sits uneasily with biblical passages such as we find in Genesis 1, Psalm 19, and Romans 1.

Genesis 1, whether one takes it literally or more poetically, most naturally suggests a God who created progressively, not simply in a solitary burst of creative action at the beginning instant of the universe. Psalm 19 plainly says that the heavens declare the glory of God, and indeed that nature pours forth testimony to his might and glory. Many centuries later, the Apostle Paul seconded this in his letter to the Romans, where he writes that the wicked are without excuse, even those who have never encountered inspired Scripture, because “what can be known about God is plain to them, because God has shown it to them. Ever since the creation of the world his invisible nature, namely, his eternal power and deity, has been clearly perceived in the things that have been made.”

Are we to assume that this was true for David standing under the stars, and for the early Christians to whom Paul wrote, but that it is somehow less true for scientists carefully studying the creation with powerful microscopes and telescopes? If nature as observed by the naked eye points plainly to God’s eternal power and deity, it does so all the more when observed with the tools of science. These tools reveal to us everything from the astonishingly fine-tuned constants of nature for life to the many astounding molecular machines we find illuminated by our most advanced microscopes, biological machines that defy evolutionary explanation. And as we probe deeper into these “machines,” we find biological information and genetic coding so advanced that Microsoft founder Bill Gates conceded that it was well beyond anything human software engineers have ever designed.3

The Crucial Step of Faith

But all this still leaves us with the objection that such evidence leaves no room for a leap of faith. For Jews and Christians who take the miracles of the Bible seriously, the objection proves too much. The Israelites who witnessed the ten plagues and walked through the Red Sea on dry ground — were they robbed of the ability to make a “leap of faith”? Not at all. They knew there was supernatural power out there, but they remained free to trust or mistrust that divine power. Many of them chose to mistrust it, to view God as every bit as mercurial and faithless as they themselves were.

Their faithlessness cost them entry into the Promised Land. As James explains in his New Testament letter, believing in the existence of God isn’t the crucial step of faith. “Even the demons believe that much,” he points out. But they don’t love and trust God. Faith, then, is much more than bare intellectual assent to the proposition that God exists. And that, in turn, means that evidence for God in nature — even powerful evidence — does not force one to have faith in the Creator.

Also, it’s clear that however powerful the evidence in nature for a cosmic maker may be, humans remain free to deny this evidence, and to heed instead whatever their itching ears want to hear. God has given us rational faculties, but we remain free to use those faculties to rationally pursue truth, or to rationalize away the truth.

Given all of the above, surely it’s shakier to guess about how God would have created things, or to conjecture about what he would or wouldn’t have chosen to reveal through nature, than simply to go to nature and see what it actually does reveal. The great founders of modern science, most of them Christians, and all of them believers in God, did precisely this.

Editor’s note: This essay originally appeared in Salvo Magazine as “Watching Our Maker,” and is republished here with permission.

Notes

- See Howard J. van Till’s “The Fully Gifted Creation,” in Three Views of Creation and Evolution, ed. J. P. Moreland and John Mark Reynolds (Zondervan, 1999), 159–218.

- The quotation, spoken by the Apostle Paul in Acts 17:28, is from a Greek poem attributed to Epimenides the Cretan.

- Bill Gates, The Road Ahead (New York: Penguin, 1996), 228.