Intelligent Design

Intelligent Design

Princeton Researchers Watch “Junk DNA” at Work

The myth of “junk DNA” may qualify as an exception to biologist Jonathan Wells’s observations about evolutionary zombies. Those are myths or icons that Darwinism refuses to abandon even after they’ve been shot to pieces by science. Dr. Wells details a selection of them in his books Icons of Evolution and Zombie Science.

Another book Jonathan wrote, The Myth of Junk DNA, stands out in that that myth looks to be in the process of being abandoned. It’s not exactly a deathless zombie, after all.

If you Google the phrase “junk DNA,” a lot of what you get are acknowledgements that non-coding DNA is not the garbage dump it was once assumed to be. The garbage dump theory was a logical and straightforward prediction in line with evolutionary expectations. That is, if evolution is an unguided process fueled by random mutations.

Instead, the “garbage” is full of “hidden treasures.” You don’t have to take our word for it.

- “Hidden Treasures in Junk DNA” (Scientific American)

- “Junk DNA — Not So Useless After All” (Time Magazine)

- “Breakthrough study overturns theory of ‘junk DNA’ in genome” (The Guardian)

- “Some DNA Dismissed As ‘Junk’ Is Crucial To Embryo Development” (NPR)

- “ENCODE Project Writes Eulogy for Junk DNA” (Science)

- “Junk DNA Isn’t Junk, and That Isn’t Really News” (Smithsonian.com)

- “DNA previously written off as ‘junk’ actually determines genitals at birth” (The Independent)

News from Princeton

Now comes news from scientists at Princeton University who have captured on video “junk DNA” at work. Its job? In “real time” they show the function of an enhancer in switching a gene from off to on. From “Imaging in living cells reveals how ‘junk DNA’ switches on a gene”:

These pieces of DNA are part of over 90 percent of the genetic material that are not genes. Researchers now know that this “junk DNA” contains most of the information that can turn on or off genes. But how these segments of DNA, called enhancers, find and activate a target gene in the crowded environment of a cell’s nucleus is not well understood.

Now a team led by researchers at Princeton University has captured how this happens in living cells. The video allows researchers to see the enhancers as they find and connect to a gene to kick-start its activity. The study was published in the journal Nature Genetics.

Analyses of how enhancers activate genes can aid in the understanding of normal development, when even small genetic missteps can result in birth defects. The timing of gene activation also is important in the development of many diseases including cancer. [Emphasis added.]

Birth defects and cancer — those are large stakes in this game. Obviously you want your “junk DNA” to be functioning properly. They go on:

As their name suggests, enhancers switch on the expression of other genes. In the mammalian genome, there are an estimated 200,000 to 1 million enhancers, and many are located far away on the DNA strand from the gene they regulate, raising the question of how the regulatory segments can locate and connect with their target genes.

Many previous studies on enhancers were conducted on non-living cells because of the difficulty in imaging genetic activity in living organisms. Such studies give only snapshots in time and can miss important details.

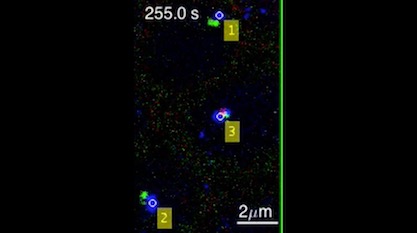

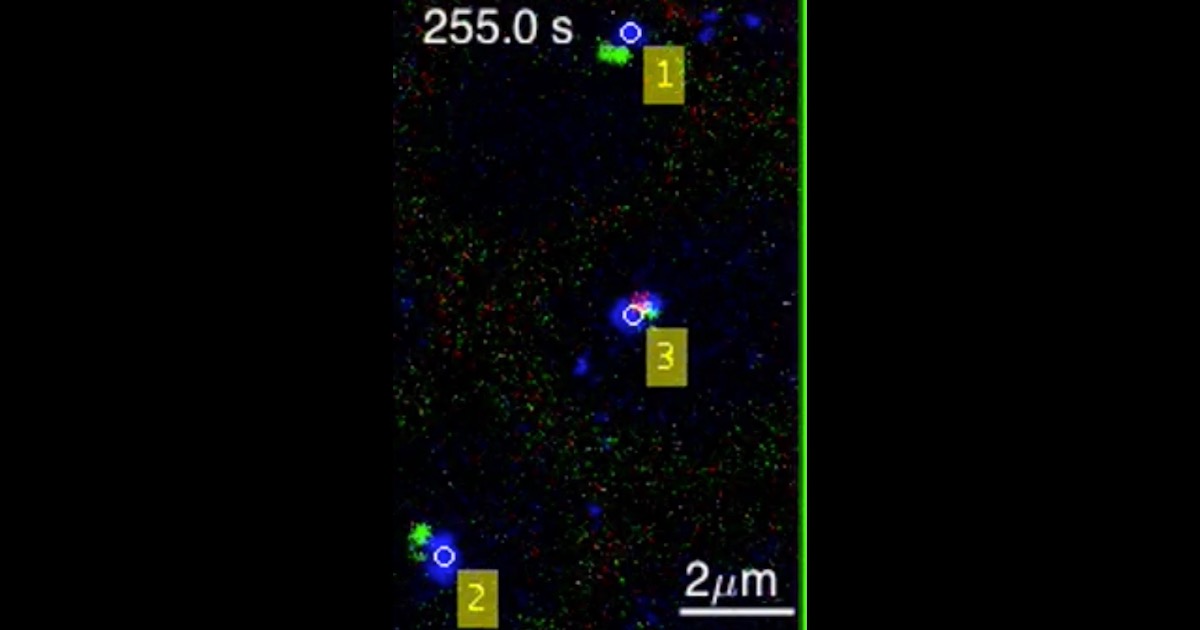

In the new study, researchers used imaging techniques developed at Princeton to track the position of an enhancer and its target gene while simultaneously monitoring the gene’s activity in living fly embryos.

Like Fingers on a Piano

It’s a bit like fingers hitting the keys on a piano. The enhancer must, in order to succeed in its task, make “physical contact.” This is challenging in what they call the “crowded environment” of the nucleus.

The video is not all that much to look at. You can see it here. They explain that the green spot is the gene, the blue one is the enhancer, and the pink or red indicates when the gene has been switched “on.” It’s remarkable that we’re able to see anything at all, however. There’s no sound track, but if there were, it might be a grumble of protest from ultra-Darwinists as they’re forced back from a once beloved evolutionary icon.

Photo credit: Hongtao Chen, Princeton University (screen shot), via EurekAlert!