Evolution

Evolution

Cited to Attack Darwin Devolves, Study Devolves on Close Inspection

UPDATED 2/25/19

Editor’s note: Because some thought that the Gauger study cited below was being offered as a refutation of the 2012 Näsvall paper (it wasn’t, and it’s not), we have updated the post to make this clear. A much fuller discussion of both papers is now provided here.

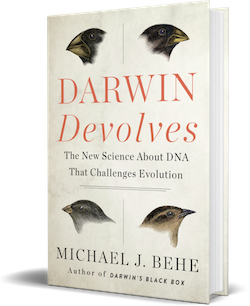

As you know, Michael Behe has a new book out later this month, Darwin Devolves: The New Science about DNA That Challenges Evolution, and the journal Science has already reviewed it. Pointing out the review’s many failings will be the work of multiple articles. Let’s start by zeroing in on just one segment late in the review.

“Overwhelming Evidence”

There, reviewers Nathan Lents, Joshua Swamidass, and Richard Lenski note that “Behe is skeptical that gene duplication followed by random mutation and selection can contribute to evolutionary innovation.” They then claim “overwhelming evidence” to the contrary, and cite a series of papers climaxing with this: “And in 2012, [Näsvall,] Andersson et al. showed that new functions can rapidly evolve in a suitable environment (11). Behe acknowledges none of these studies, declaring an absence of evidence for the role of duplications in innovation.”

Others can weigh in on the other papers cited in that paragraph. But biologist Wayne Rossiter emailed with a note about the 2012 Näsvall paper. “For those who weren’t aware, the 2012 study mentioned in the review (reference 11) was… debunked by Matti Leisola (and his co-author Jonathan Witt) in his wonderful book, Heretic: One Scientist’s Journey from Darwin to Design. It’s a must have for anyone’s ID library.”

From Chapter 9 of Heretic

The excerpt below includes the section from Chapter 9 of Heretic that Rossiter refers to, plus discussion of another experiment by Gauger et al:

The most impressive evolutionary experiment to my knowledge so far reported was carried out by an international team using Salmonella enterica. On October 22, 2012 a report claimed that this was the first time a group demonstrated the origin of a new gene. In reality a gene with a weak side-activity was duplicated and the side-activity was strengthened. Intriguing, but nothing more — and nothing new. Yet what follows is how the work was described in the popular press (emphasis added to show where intelligent engineering was introduced into the experimental environment):

“Researchers engineered a gene that governed the synthesis of the amino acid histidine, and also made some minor contributions to synthesizing another amino acid, tryptophan. They then placed multiple copies of the gene in Salmonella bacteria that did not have the normal gene for creating tryptophan. The Salmonella kept copying the beneficial effects of the gene making tryptophan and over the course of 3,000 generations, the two functions diverged into two entirely different genes, marking the first time that researchers have directly observed the creation of an entirely new gene in a controlled laboratory setting.”

There has been another interesting evolution experiment carried out using E. coli. The theoretical background to the experiment is as follows. It is generally assumed that a multi-step mutational evolutionary path is possible if all the intermediary steps are functional and can each be reached by a single mutation. The activity produced in this way may, however, be so weak that the cell must over-express the hypothetical newly formed enzyme — in other words, produce too much of the enzyme, causing a huge strain on the cell because it has to use extra synthetic capacity for this. Therefore it is likely that the cell would shed such a weak side-activity. The modest benefit wouldn’t be worth the strain caused by the overproduction.

Ann Gauger and her colleagues studied what happened in such a case under laboratory conditions. They introduced a mutation that partially interfered with a bacterial cell’s gene for the synthesis of the amino acid tryptophan. Then they introduced a second mutation into the gene that completely abolished the ability to synthesize tryptophan. Cells with the double mutant could, theoretically, regain weak tryptophan-synthesizing ability with only one back-mutation. Given more time, cells with the one back-mutation might then undergo one more back-mutation to regain full tryptophan-synthesizing ability. This might demonstrate how a cell could gain a new function with just two mutations. But this did not happen. Instead, cells consistently acquired mutations that reduced expression of the doubly mutated gene. The experiment suggests that even if the cell could acquire a weak new activity by gene mutation, it would get rid of it because weakly performing functions of this sort exact too heavy an energy burden.

So, while the described experiments are often promoted as evidence for neo-Darwinian evolution, they either (a) are intelligently designed and do not accurately reflect what happens in nature, or (b) underscore the narrow limits of neo-Darwinian evolutionary change.

Specifically, the Näsvall et al. experiment reflects scenario a, and the Gauger et al. experiment reflects scenario b. (Again, a much fuller discussion of both experiments can be found here.)

Behe’s new book is available for pre-order now. And while you are waiting, check out Heretic, by Witt and distinguished Finnish bioengineer Matti Leisola.

Photo: Michael Behe, in Revolutionary: Michael Behe and the Mystery of Molecular Machines.