Evolution

Evolution

Life Sciences

Life Sciences

Nature Communications Retroactively Concedes a Lack of Evidence for Darwinian Gradualism

Years ago I began to recognize a repeating phenomenon in the rhetoric of evolutionary literature: Scientists, echoed by science journalists, would only admit a problem with their models or a challenge to their ideas once they thought they had found a solution. I’ve called these “retroactive admissions of ignorance.” We now have another example of this, from a paper just published in Nature Communications purporting to demonstrate Darwinian gradualism: “General statistical model shows that macroevolutionary patterns and processes are consistent with Darwinian gradualism.” Retroactive admissions of ignorance, weakness, or other problems typically come in the first sentences of the abstract or introduction of a paper. The rest of the paper is then supposed to show why the admission no longer applies, as the weakness has been cleared up. This paper is no exception to the pattern. From the abstract:

Macroevolution posed difficulties for Darwin and later theorists because species’ phenotypes frequently change abruptly, or experience long periods of stasis, both counter to the theory of incremental change or gradualism.

The paper continues:

The abrupt phenotypic changes observed in the fossil record and inferred on phylogenies are often seen as challenges to Darwinian gradualism, being attributed to occult forces such as quantum changes, macromutations and megaevolution, or phenomenologically to special jumps processes embodied in fat-tailed distributions or Levy processes.

Likewise Science Daily reports:

Abrupt shifts in the evolution of animals — short periods of time when an organism rapidly changes size or form — have long been a challenge for theorists including Darwin.

Now They Tell Us

That sounds reasonable. Science Daily goes on to state that when we think we see the abrupt appearance of new forms, in reality the paper shows that “even these abrupt changes are underpinned by a gradual directional process of successive incremental changes, as Darwin’s theory of evolution assumes.” The paper claims that statistical analysis of what seem to be abruptly appearing traits shows the evolution is actually gradual in nature. They argue that “large or abrupt phenotypic shifts are explicable statistically as biased random walks, allowing macroevolutionary theory to engage with the language and concepts of gradualist microevolution.” The paper even claims that it can reconcile macroevolutionary trends with microevolutionary processes:

But our results show that the directional changes we infer can arise from the ‘ordinary’ incremental mode of Darwinian evolution available to an existing genetic system, without requiring any alteration to that system’s ability to produce new mutational variants. This is an important result, providing a way for macroevolutionary theory to make progress by engaging directly with well-understood concepts and measurable phenomena that occur at the microevolutionary level.

The problem with many retroactive admissions of ignorance is that their resolutions don’t live up to the promise. In other words, evolutionists concede problems with their theory only because they feel secure that they’ve come up with a solution. But if that solution doesn’t do the job, then the condition of ignorance remains. That seems to be exactly what has happened here.

What’s the Evidence?

So what is the paper’s evidence that “short periods of time when an organism rapidly changes size or form” are actually consistent with gradual evolution? According to the paper, they only sought to study rates of evolution in a single trait — body size in mammals:

We apply the Fabric model here to the evolution of body size in mammals, a Class particularly suitable for macroevolutionary study owing to its wide morphological variation and ecological specialisations.

The problem with using body size as a metric of the rates or the gradual creative power of evolutionary mechanisms is that we already know body sizes are highly malleable. So finding evidence of finely gradated changes in body size is not news. I mentioned this recently when covering the horse fossil series, where horses throughout the sequence undergo little morphological change apart from in body size.

As another example, consider humans alive today. You could line up humans who are athletes in various sports — from horse jockeys to gymnasts to volleyball players to basketball players, and everything in between. You would find a nice, smooth gradual spectrum of body sizes. And it would all represent variation within a species. So if we can find finely gradated and widespread variation of body sizes within a single living species, then it’s not too surprising that we might find gradual changes in body sizes in the fossil record.

The point is that slight, gradual changes in body size — scaling up or down in what you already have — are very easy to evolve, and are prevalent throughout many animal species. But changing body sizes is very different from producing novel anatomical features. An analogy might help appreciate why this is the case.

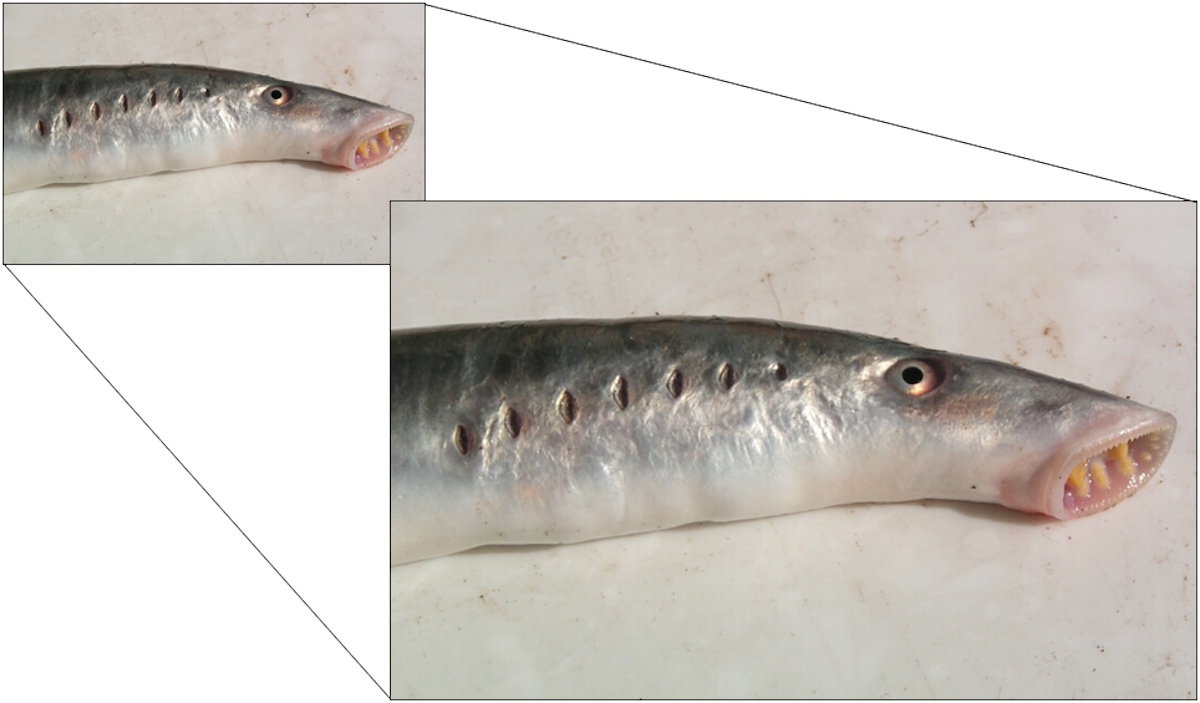

Consider the jawless fish — a lamprey — pictured at the top of this article. Let’s say you copy the image, and paste it into PowerPoint (or a similar program). Using such a program it’s a simple procedure to gradually resize the image, maintaining its scale and basic shape as it grows larger or smaller. You’re just scaling what you’ve already got, in constant proportions.

OK, that was easy! But now try this with the image: Draw plausibly functional jaws on the jawless lamprey. Doing this will require great skill and creativity as a graphic artist, a sophisticated graphic design program, as well as a keen knowledge of vertebrate biology.

The point? It’s a lot easier to change the size of an organism than it is to add a fundamentally new feature to it.

Evolving Real Novelty

In light of these points, my colleague Paul Nelson makes the following comment about the import of this paper:

Body size in mammals is not the sort of phenotypic trait that heterodox evolutionary theorists such as Richard Goldschmidt, or more recently, Stephen Jay Gould or Jeffrey Schwartz, worried about as inexplicable under neo-Darwinian gradualism.

Indeed, many scientists have expressed concern that neo-Darwinian mechanisms cannot account for the origin of truly novel anatomical features. We’re not talking about things like changes in body size — different sizes of things you’ve already got. We’re talking about the origin of new body plans and structures with novel anatomical functions. As Richard Goldschmidt wrote in his 1940 book from Yale University Press, The Material Basis of Evolution:

I may challenge the adherents of the strictly Darwinian view, which we are discussing here, to try to explain the evolution of the following features by accumulation and selection of small mutants: hair in mammals, feathers in birds, segmentation of arthropods and vertebrates, the transformation of gill arches in phylogeny, including the aortic arches, muscles, nerves, etc.; further, teeth, shells of mollusks, ectoskeletons, compound eyes, blood circulation, alternation of generations, statocysts, ambulacral system of echinoderms, pedicellaria of the same, cnidocysts, poison apparatus of snakes, whalebone, and, finally, primary chemical differences like hemoglobin vs. hemocyanin, etc. Corresponding examples from plants could be given.”

Richard Goldschmidt, The Material Basis of Evolution, pp. 6-7

The More Things Change…

Evolutionary biology has undoubtedly changed since Goldschmidt’s time, but biologists in a modern context have said much the same thing as he did. Jeffrey Schwartz of the University of Pittsburgh notes that even those who were upset with Goldschmidt’s arguments could not produce a viable evolutionary mechanism for generating new body plans:

In the midst of his outpouring of anger at and dismissal of Goldschmidt, Dobzhansky neglected to consider the fact that while Goldschmidt’s systemic mutations may not have been observed, neither had the mechanisms of speciation that he, or anyone else, for the matter, had proposed. Rather, Dobzhansky, as others did and would do, took for granted that, with enough time, the kinds of small mutations and changes that were observed in laboratory experiments on fruit-fly population genetics were also capable of producing the degrees of differences that seem to characterize species in the wild. To be sure, there was a certain logic in the belief that it was unnecessary to postulate another mechanism for evolutionary change when one already appeared to exist. This logic also seemed to benefit from the assertion that not only had no other mechanism been observed but that no other mechanism had yet produced species. Nevertheless, it was and still is the case that, with the exception of Dobzhansky’s claim about a new species of fruit fly, the formation of a new species, by any mechanism, has never been observed.

Jeffrey H. Schwartz, Sudden Origins: Fossils, Genes, and the Emergence of Species, John, Wiley & Sons: New York NY, 1999, pp. 299-300

Echoing this refrain, Robert Carroll’s Cambridge University Press 1997 book, Patterns and Processes of Vertebrate Evolution, observes that evolutionary biologists still struggle to explain how novel biological features arise:

The following phenomena are of particular concern to biologists:

1. The origin of major new structures: Biologists have long struggled with the conceptual gap between the small-scale modifications that can be seen over the short time scale of human study and major changes in structure and ways of life over millions and tens of millions of years. Paleontologists in particular have found it difficult to accept that the slow, continuous, and progressive changes postulated by Darwin can adequately explain the major reorganizations that have occurred between dominant groups of plants and animals. Can changes in individual characters, such as the relative frequency of genes for light and dark wing color in moths adapting to industrial pollution, simply be multiplied over time to account for the origin of moths and butterflies within insects, the origin of insects from primitive arthropods, or the origin of arthropods from among primitive multicellular organisms? How can we explain the gradual evolution of entirely new structures, like the wings of bats, birds, and butterflies, when the function of a partially evolved wing is almost impossible to conceive?

Robert Carroll, Patterns and Processes of Vertebrate Evolution, pp. 8-10 (Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press, 1997)

Note that Carroll isn’t referring to mere change in body sizes or coloration. He’s referring to the origin of body plans themselves or of “entirely new structures” like the wings of types of various organisms. Changing body size or colors is a form of adaptation that no one denies. Generating entirely new structures is where an evolutionary model will sink or swim.

In 2008, biologists at what has come to be called the Altenberg 16 conference discussed deficiencies in modern evolutionary theory. Although some denied that neo-Darwinism was in crisis, embryologist Scott Gilbert was quoted in a Nature report on the conference saying that “[t]he modern synthesis is remarkably good at modeling the survival of the fittest, but not good at modeling the arrival of the fittest.” Likewise, evolutionary paleobiologist Graham Budd stated: “When the public thinks about evolution, they think about the origin of wings and the invasion of the land, . . . [b]ut these are things that evolutionary theory has told us little about.”

The following year, Günter Theißen of the Department of Genetics at Friedrich Schiller University in Germany wrote in the journal Theory in Biosciences that “while we already have a quite good understanding of how organisms adapt to the environment, much less is known about the mechanisms behind the origin of evolutionary novelties, a process that is arguably different from adaptation. Despite Darwin’s undeniable merits, explaining how the enormous complexity and diversity of living beings on our planet originated remains one of the greatest challenges of biology.”

“What Darwin Got Wrong”

The next year, in their book What Darwin Got Wrong, Jerry Fodor and Massimo Piattelli-Palmarini recognized that the origin of new animal body plans cannot be explained by gradual Darwinian processes. The authors, both self-identified evolutionists and atheists, wrote:

Davidson and Erwin (2006) argued that known microevolutionary processes cannot explain the evolution of large differences in development that characterize entire classes of animals. Instead, they proposed that the large distinct categories called phyla arise from novel evolutionary processes involving large-effect mutations acting on conserved core pathways of development. Gene regulatory networks are also modular in organization (Oliveri and Davidson, 2007). This means, in essence, that they form compact units of interaction relatively separate from other similar, but distinct, units.

The consequence is that these processes make the connection between specific biological traits, specific evolutionary dynamics and natural selection very complicated at best, impossible at worst. In the words of a leading expert of gene regulatory networks:

“Developmental gene regulatory networks are inhomogeneous in structure and discontinuous and modular in organization, and so changes in them will have inhomogeneous and discontinuous effects in evolutionary terms … These kinds of changes imperfectly reflect the Class, Order and Family level of diversification of animals. The basic stability of phylum-level morphological characters since the advent of bilaterian assemblages may be due to the extreme conservation of network kernels. The most important consequence is that contrary to classical evolution theory, the processes that drive the small changes observed as species diverge cannot be taken as models for the evolution of the body plans of animals. These are as apples and oranges, so to speak, and that is why it is necessary to apply new principles that derive from the structure/function relations of gene regulatory networks to approach the mechanisms of body plan evolution.

“Davidson, 2006, p. 195, emphasis added.”

Jerry Fodor and Massimo Piattelli-Palmarini, What Darwin Got Wrong, pp. 40-41

In 2014, when critiquing Stephen Meyer’s book Darwin’s Doubt, biologist and theistic evolutionist Darrel Falk, a prominent critic of intelligent design and former president of the BioLogos Foundation, summarized the state of the field. He acknowledged that evolutionary biologists still don’t understand how new body plans arose:

The big mystery associated with the Cambrian explosion is the rapid generation of body plans de novo. There was never a time like it before, nor has there ever been a time like it again since. Stephen is right about that. Also, as he points out, the big question in exploring the generation of new body plans in that era is how this squares with the resistance of today’s gene regulatory networks to mutational perturbation (i.e. they seem to be almost impossible to change through genetic mutation because virtually all such alterations are lethal). We really have little idea at this point how things would have worked to generate body plans de novo back then given the sensitivity of the networks to perturbation today.

Then, in 2016 the Royal Society held a now infamous meeting, “New trends in evolutionary biology: biological, philosophical and social science perspectives,” where various speakers critiqued the modern synthesis. In the opening lecture of the conference, Austrian biologist Gerd Müller declared that the modern synthesis “does not explain” things that he calls “complex levels of evolution” such as “the origin of these body plans,” as well as “complex behaviors, complex physiology, development.” He explains that “the standard theory is focused on characters that exist already and their variation and maintenance across populations, but not on how they originate.” He says the theory is “not designed for addressing” the origin of novel characters. As Paul Nelson explained in a podcast, these problems were never resolved at the conference.

The point is that while this recent Nature Communications paper purports to find evidence of gradual evolutionary change in mammalian body size, that’s not something that would surprise anyone in light of the diverse spectrum of body sizes that often exist even within a species at any given time. Change in body size, even gradual evolutionary change, does not represent the kind of novel body plans or novel phenotypic traits that the neo-Darwinian model struggles to explain.

…The More They Stay the Same

As a final note, just because one study finds evidence for gradual change in one trait, that doesn’t mean such change is the rule in the fossil record. In fact, it’s not the rule. The same week another new paper came out in the Nature journal Communications Biology, “An exceptionally preserved Sphenodon-like sphenodontian reveals deep time conservation of the tuatara skeleton and ontogeny.” The paper concludes that tuataras (lizard-like reptiles from New Zealand) have experienced stasis and virtually no change over at least the last ~190 million years:

Comparisons with Sphenodon reveal that fundamental patterns of mandibular ontogeny and skeletal architecture in Sphenodon may have originated at least ~190 Mya. In combination with recent findings, our results suggest strong morphological stability and an ancient origin of the modern tuatara morphotype.

Explaining the origin of complex phenotypic novelty is the million-dollar question in evolutionary biology. (Perhaps with inflation it should be called the billion-dollar question.) This question may one day be answered, but that day has not yet come, and the studies cited here do little to move the field in that direction.

Thanks to Paul Nelson for his insights for this post.