Evolution

Evolution

Intelligent Design

Intelligent Design

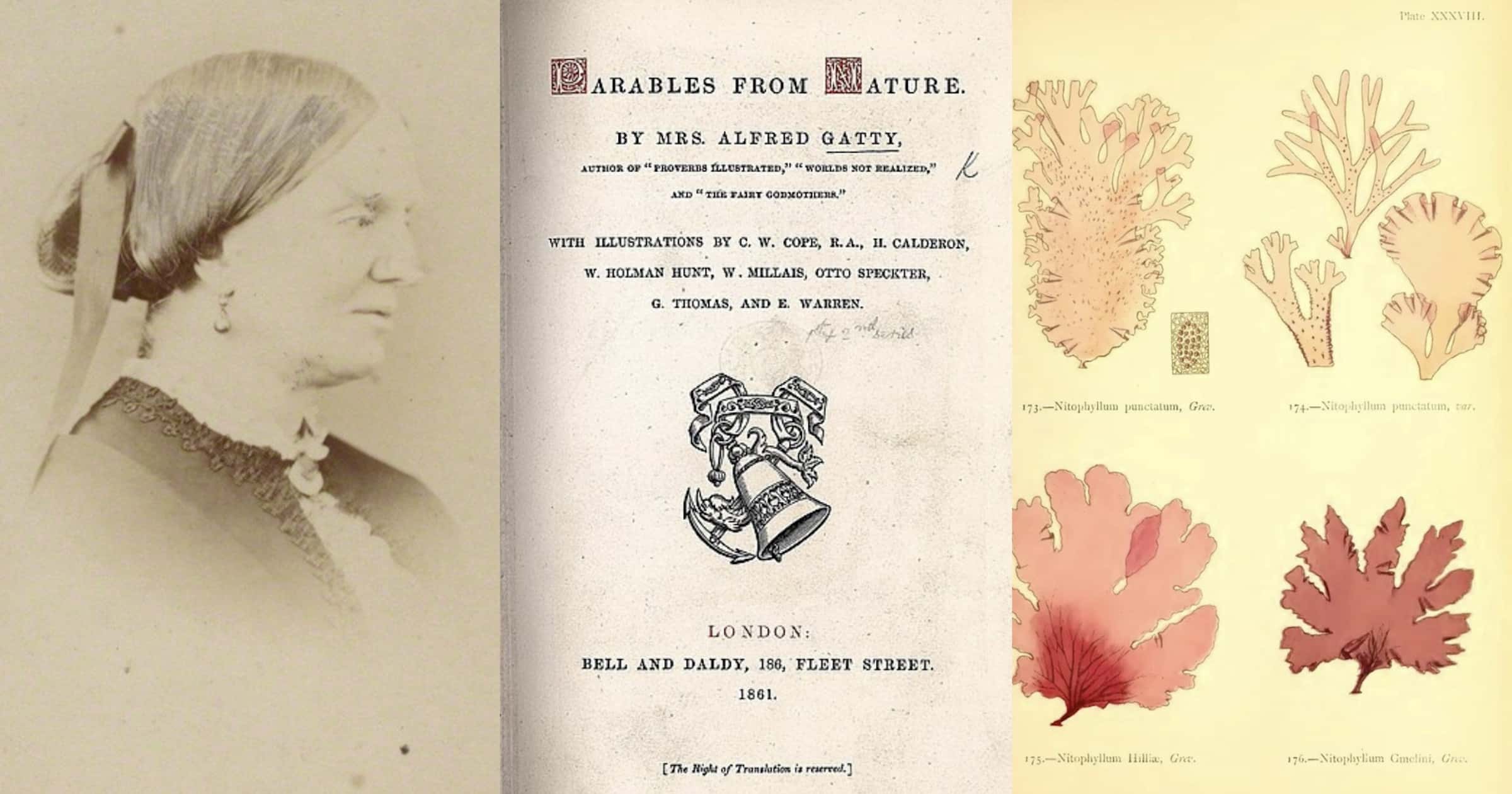

Parables from Nature: A Profile of Margaret Gatty

If you’ve been listening to ID the Future or reading our work at Evolution News, you’ll likely be familiar with the growing evidence of design in nature. As biochemist Michael Behe has put it, we are living through a revolution in molecular biology, brought about by advances in the last century of technology that has allowed us to see inside the cell, that black box that Charles Darwin and his contemporaries were not yet able to comprehend. Today we know the cell contains layer upon layer of complexity and design — veritable factories full of precision-engineered protein machines that perform the functions of life.

In his 1996 landmark book Darwin’s Black Box, Dr. Behe wrote that to appreciate the complexity behind life, we have to experience it. For the last half century and more, that’s exactly what we’ve been able to do. In the face of this evidence of complexity and design, more and more biologists are finding it untenable to maintain that gradual evolutionary processes like natural selection could be responsible for such remarkable feats. Some are calling for a new theory of evolution. Some are jumping ship and shifting to a design perspective, opening up new questions and avenues for research, even as they may suffer professionally for their boldness. And some, too afraid to rock the boat, continue to put their faith in a dying theory.

Darwin the Man

Lately, I’ve been interested in learning more about Charles Darwin — the man, not the mythological character — as well as Darwin’s time, and those who lived through his era. I’m hoping to gain insight into why he put so much faith in natural processes to account for the origin and complexity of life. This month, we’re unveiling a new book by Robert Shedinger, Darwin’s Bluff: The Mystery of the Book Darwin Never Finished. Shedinger refers in his title to the sequel to On the Origin of Species that Darwin promised but did not deliver. Darwin called his Origin of Species a mere abstract, and this sequel would finally supply solid empirical evidence for the creative power of natural selection, evidence he admitted was absent from the Origin. In looking at why Darwin abandoned his book, Shedinger reveals a Darwin just as human as the rest of us, subject to the same misconceptions and frailties as we are. In anticipation of Shedinger’s book, I want to profile a woman who was Darwin’s contemporary, was a naturalist as he was, but had a very different view on the origin and development of life.

Margaret Gatty was born in 1809, the same year as Charles Darwin. Her birthplace was Burnham-on-Crouch, a small coastal town near London in the southeast of England. Darwin was born 200 miles to the west, in Shrewsbury, near the Welsh border. Margaret’s father, the Rev. Alexander Scott, was a naval chaplain and friend to Admiral Lord Nelson until Nelson’s death at the Battle of Trafalgar. Scott was known to have had a floating library of hundreds of books. Tragically, Margaret’s mother Mary died when Margaret was just two years old and her sister Horatia three. Her father consoled himself with his book collection for many years. They “flooded the sitting-rooms, and crept up the stairs, and lined a long gallery, and overflowed into the bedrooms.” To her father, learning was a labor of love, and he encouraged his daughters to learn from the books he had amassed.

An Interest in Marine Biology

Margaret grew interested in marine biology through a second cousin, Charles Gatty, a Royal Society member. She also learned to draw and etch and was fond of studying the illustrations and collections at the British Museum. Not content to learn only from books, she began a lifelong habit of corresponding with eminent naturalists, including William Henry Harvey, George Johnston, and Robert Brown. George Johnston, a Scottish naturalist, would have particularly inspired her in her scientific interests. He encouraged women to take part in natural history study and the collecting of specimens. “We must not forget the women,” he insisted.

In 1839, Margaret married author and Reverend Alfred Gatty. Like her parents’ marriage, it was a union founded on shared aims and pursuits, and her husband encouraged her to continue her work in writing and natural history. She acquired a growing collection of seaweeds and marine invertebrate specimens — known at the time as zoophytes: sponges, corals, sea anemones, comb jellies, and the like. In the 19th century it was debated whether these organisms were plants, or animals, or both. In 1855, Margaret published the first volume of what would be her most famous work: Parables from Nature, a collection of stories in parable form written for young people, all featuring personified characters from the natural world. A second volume of her parables came in 1857, among her other published works.

Not a New Idea

And then, in 1859, Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life, an abstract of his theory that populations of organisms evolve over generations through a process of natural selection. The concept of evolution was not new. Transmutation — one species transforming to another — was an established topic of much controversy, and even natural selection was already in currency before Darwin’s book. Scottish farmer and grain merchant Patrick Matthew, for example, discussed the concept of natural selection in a book about timber in 1831, 29 years before Darwin published On the Origin of Species. Matthew called natural selection “the modification of life to circumstances,” and didn’t make much of it, considering it a “self-evident fact.” Matthew held that organisms possessed a “variation power,” but he also recognized a “principle of beneficence” and a “principle of beauty” in living things that he argued “cannot be accounted for by natural selection.” Darwin, however, thought differently, staking his reputation on the seemingly limitless power of natural selection to explain the development as well as the diversity of life.

Although she refrained from challenging Darwin publicly, Margaret had strong thoughts of opposition to Darwin’s proposals, and shared them privately amongst family, friends, and her correspondents. In 1861 she published a third series of Parables from Nature and followed that with the publication in 1862 of her major scientific work, British Seaweeds, a culmination of 14 years of experience that contained over 200 of her own illustrations. She published a fourth series of parables in 1863, with the final set arriving in 1870. For almost a decade, Margaret suffered from a sort of paralysis that constrained the use of her limbs and even her speech. This did not deter her, though, and she continued to write through dictation, publishing her last two books in 1872 with the help of her husband, including a book detailing her life-long collection of sundials and their curious mottos. Margaret died in 1873.

In a brief memoir of her mother’s life that accompanies later editions of Parables from Nature, Margaret Gatty’s daughter Juliana Horatia Ewing, a noted author herself, wrote of her mother that she took “a child’s pure delight in little things.” Perhaps that is why much of Gatty’s writing was directed to the young. In illuminating the particularities of living things — many of them small and considered by some as insignificant creatures — through her stories and drawings, Gatty has inspired generations of young people with the natural history of the world.

“Inferior Animals”

In some of her parables written in the aftermath of Darwin’s Origin of Species, Margaret indirectly criticized what she saw as the hubris of Darwin’s theory. One parable tackles the issue closely — “Inferior Animals” — and I’d like to share a few excerpts here.

At the beginning of the parable, the speaker invites the reader to “become children in heart once more”: “let us go forth into the fields and read the hidden secrets of the world.” The speaker comes across a large gathering of rooks in a field. Rooks are large, black birds native to Europe, similar to ravens. Here, the speaker issues a challenge to the learned of the world: “Hear this, oh you philosophers — you lights of the world, with your books and papers and diagrams, and collected facts, and self-confidence unlimited! You who turn the bull’s-eye of your miserable lanthorns upon isolated corners of the universe, and fancy you are sitting in the supreme light of creative knowledge!” Can you explain what the rooks are doing and saying, why they gathered, and by what methods they called the gathering?

Suddenly, the spell is broken, and what was the noisy cawing of the birds turns into a language that the speaker understands and relates to the reader. The rooks, it turns out, have gathered to hear one particular rook discuss the origins of Man. Thanks to a “spirit of inquiry” this rook no longer believes in the superiority of humans, instead putting it down to mere myth, to “the delusion of timid minds.” The rook goes on to provide evidence of man’s ancestry, a degenerated cousin of the bird race, and inferiority — his inability to fly, his need to cover his body with clothes, his wanton cruelty to other beings, his restless dissatisfaction. “Behold him — a featherless, thin-skinned biped.” Over time, with lack of use and with the accumulation of bad habits and laziness, humans have turned into a different creature. “But heap ages upon ages, and other ages upon them…anything is possible in the course of such a period.” And here, the rook echoes the confident tone of Darwin in the Origin of Species: “But what cannot we flatter ourselves we have proved,” continues the bird, “when our minds are warped by a theory!”

In his speech, the rook employs a scientistic perspective — the idea that science can and will explain everything, in time, and that science is our only source of knowledge and wisdom. “This is a bold proposition,” admits the rook, “and I do not ask you to assent to it at once. But…if things are not so, how are they? For remember we have already laid down the maxim, that everything ought to be and can be explained.”

The rook then claims that humans are striving once again to re-associate themselves with the original bird race. And just as he begins discussing what the response of the rooks should be, the scene suddenly changes again. All the birds are gone. The field is quiet, and the speaker is alone again, awaking as if from a dream. The parable closes with the speaker’s reflections: “Woe upon us! The world grows old, and life is repeated from age to age, and the same sins are sinned…still we desire to be as God in knowledge.”

The Wisdom of Socrates

With this parable, Gatty seems to be making a case for a child-like faith and curiosity toward Nature, a contrast to the attitude of some of the well-educated of her time who thought they had it all figured out. It reminds me of the wisdom of Socrates, and his admission that what made him wise was his awareness that he knew practically nothing. Socrates understood the limits of human knowledge and questioned the certainty of our beliefs and opinions. It seems paradoxical, to go in search of knowledge while being willing to admit we don’t know much. But if honesty is to be at the heart of our scientific pursuit, then humility must be in good supply, an awareness that we may not grasp the full extent of reality outside the fullness of time.

Through her study and writing, Margaret Gatty promoted curiosity, reverence, and zest for nature, while at the same time encouraging people in the noble principles of living that she herself lived by. She deserves to be remembered as a contemporary of Darwin who recognized the intelligent design of living things and worked tirelessly to share it with others.