Evolution

Evolution

Intelligent Design

Intelligent Design

Life and Origami: Lessons from the Art of Paper-Folding

As a child I used to enjoy making origami figures, including cranes, boats, planes, butterflies, and flowers among others. These were simple, typically requiring no more than a few minutes of my time and a couple dozen steps at most.

Now, one of my children makes complex and realistic origami critters that require close to 200 steps. The image at the top, in fact, is an origami Cyclommatus metallifer beetle made by Isaac Gonzalez. The design is from Works of Satoshi Kamiya 2. It has 184 steps and is classified as complex (the highest rating is super complex).

In its purest form origami involves only folding — no additions, subtractions, tearing, or cutting. A few origami crafters will sometimes use glue to keep the model in its final form for display. Further, the starting point is a square piece of paper. This avoids any bias in starting with a shape that might resemble the final product. The folds must be very precise and cannot be sloppy, or it will fail. There are several specific types of folds: valley, mountain, sink, and squash folds. Making a complex origami figure can take from hours to days.

Often, the crafter first makes a pre-crease pattern, which serves as the guidepost for the folding steps. You can think of an origami figure as containing information, which would be the folding steps that transformed the 2D piece of paper into a 3D shape. The crease pattern is the final model, unfolded, with all the major folds. The crease pattern would be a subset of the total information content, since the crease pattern by itself is not enough to create the end product.

At its core, origami is about planning and precision. An origami designer envisions a complex 3D structure and then works backward to determine the necessary folds to achieve that form. Each crease and fold must be meticulously planned, often requiring a deep understanding of geometry and spatial reasoning. The designer must consider how layers of paper interact, how tension and flexibility affect the structure, and how to balance simplicity with complexity. Not surprisingly, the more detailed the final model, the greater the number of folding steps.

A Developing Organism

In a sense, origami is a simple illustration of the development of an organism. An organism starts with the information contained in the 1D sequence of nucleotides in DNA (plus epigenetic information) and develops into a 3D structure. Aspects of origami are also present in a couple of places along the way. One is the folding of an amino acid sequence into the functional 3D structure of a protein. During embryonic development, certain proteins trigger precise folding patterns in tissues — like how the neural tube folds to form the early brain and spinal cord.

The differences between an origami figure and a living thing are more instructive than their similarities. Of course, an origami figure is a dead static thing, while a living thing is, well, alive. A living thing contains not only the instructions but also the means to make another living thing. An origami artist must create the design and then execute it on a piece of paper. An origami figure can’t make itself.

Yet no matter how masterfully crafted, these remain abstractions — creative interpretations rendered in paper that capture form but not substance. I think the real lesson origami teaches us about living things is the amount of planning, design, and effort that goes into making something that merely superficially resembles a living thing. How much more, then, for the design of a living thing?

AI and Origami

I would argue that just as an origami figure is a faint shadow of the living thing it represents, so is AI just a superficial imitation of the human mind. Large language models can do impressive things, but they are created by creatures with actual minds, who don’t understand how their minds work. We have made algorithms, trained on data from our creations, that produce outputs resembling human language, art, and music. It’s almost like origami in reverse; these creations are ultimately flattened reflections of our own intellectual and creative endeavors. They cannot fully embody our capacity for lived experience, emotional nuance, or genuine understanding.

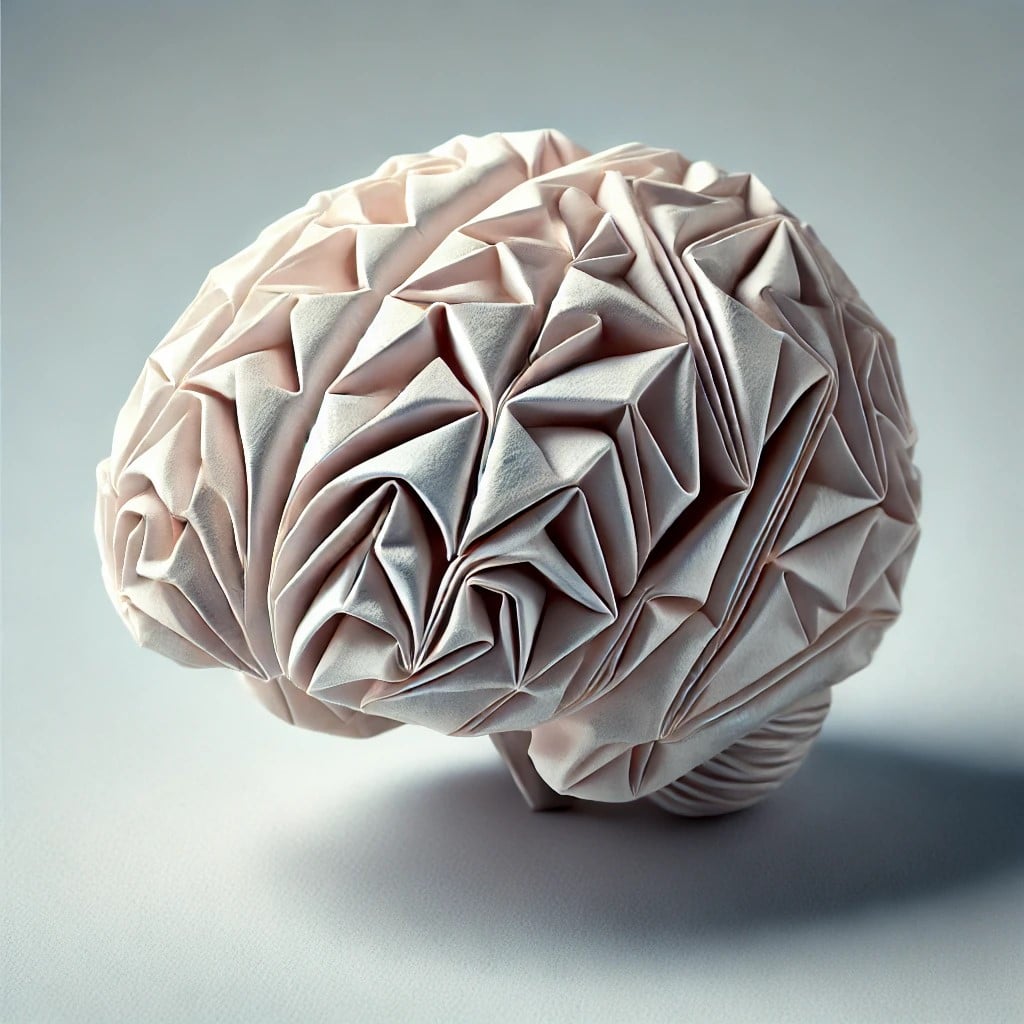

When we appreciate a finely crafted origami figure, we understand that its beauty and semblance of life come from the artist’s vision and manual skills. AI, likewise, depends entirely on the data, insights, and patterns that human minds have cultivated over generations. The illusions of creativity and spontaneity it may produce are drawn from a vast archive of human achievements. But like origami figures, AI LLMs are ultimately elaborate simulations — products of human ingenuity that mimic rather than replicate the true nature of intelligence. The AI-generated illustrations in this post are not formed ex nihilo. Instead, they are collages of fragments drawn from a vast number of human-made images, refashioned into something that seems novel but still bears the imprint of its human heritage.

Our Unique Creativity

Recognizing this relationship invites us to reflect on what makes our own creativity unique. The wonder of our thoughts lies not only in what we produce, but in how we perceive, question, and emotionally engage with the world. AI may piece together a beautiful picture or craft a clever sentence, but it lacks the ability to truly understand the meaning behind those outputs or experience the flash of insight that leads to genuine innovation. Like the folded paper crane, it cannot break from the inherent flatness of its architecture.

Yet this shouldn’t diminish our appreciation of AI’s role. As creators, we supply the “paper” and the “folds” — the data and the algorithms — and what emerges can be deeply impressive. The challenge, for the future, is to remain aware of AI’s limitations, even as we admire its capabilities. By doing so, we preserve our sense of human identity and agency — recognizing that the subtle sparks of life that animate our creativity remain distinctly our own.

This distinction becomes particularly important as AI systems become more capable and their outputs more convincing. Just as we can appreciate the beauty of origami while understanding its fundamental difference from living creatures, we must maintain a clear-eyed view of AI’s capabilities and limitations. These are powerful tools that extend human creativity and capability, but they are not conscious beings with genuine understanding.

The origami metaphor reminds us that imitation, no matter how sophisticated, is distinct from the real thing. As we continue to develop and deploy AI systems, this awareness helps us maintain appropriate expectations and use these tools responsibly — appreciating their capabilities while recognizing their fundamental nature as elaborate simulations rather than truly intelligent entities.