Evolution

Evolution

Intelligent Design

Intelligent Design

With One Short Rule, Philip Ball Explains Why “Junk DNA” May Be a Placeholder for Ignorance

Imagine you are an ambitious young genetics postdoc. You are not particularly interested in – or maybe even strongly opposed to – the idea of intelligent design. But you really want to discover something new in your field. Turning up an unexpected and dramatic finding is the best path to a tenure-track job in genetics, and funding.

Then you hear the following story.

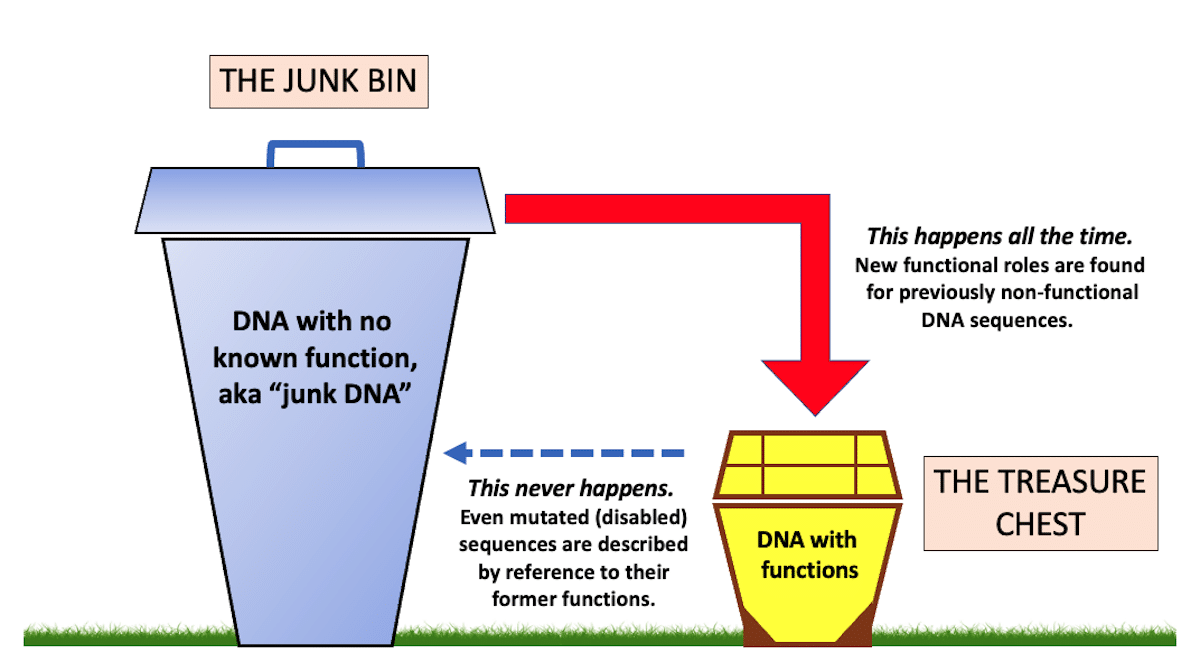

Two Containers — With Only One-Way Traffic Between Them

Out on the lawn sit two containers: a large waste bin and a smaller treasure chest (see the illustration). The bin is labelled “DNA with no known function, aka junk DNA.” The treasure chest has the label “DNA with functions.” Curious, we inspect these two containers daily for months. We notice that DNA sequences are regularly being moved from the larger into the smaller container — but never in the other direction. DNA labeled as non-functional may on closer investigation turn out to have functions. Once a role has been assigned to a sequence, however, and it is placed in the functional treasure chest, there it stays. All the traffic flows in one direction.

The Problem with Negatively Defined Categories

Well, sure, you reply, after listening to this vignette. That is the inevitable problem with any negatively defined category, such as “no known function.” Non-function can never be established with certainty. Logically, by its very nature, the designation of “no known function” is just waiting to be overturned on further investigation. This may happen with the first observational counterexample or with a novel experimental approach.

Junk DNA proponent Larry Moran, a University of Toronto biochemist, acknowledges this in the opening of his 2023 book What’s In Your Genome? 90 Percent of Your Genome Is Junk. “I cannot prove that most of our genome is junk,” he writes (pp. 5-6), “because it’s almost impossible to prove that something does not have a function — that’s the well-known problem of ‘proving a negative.’” Thus, “non-functional DNA,” especially when adopted as a null hypothesis, always remains at best a provisional — i.e., a wastebasket — category. Sequences can travel from the waste bin into the treasure chest, but never the other way around. Even the many sequences in the treasure chest that are observed to have disabling mutations are explained by reference to their previous functions, now disrupted by (for instance) an in-frame stop codon.

And most strikingly, “no known function” assertions turn out to be wrong pretty much every other week. This is signaled in the primary research literature by papers opening with a sentence such as “Sequence x, once thought to be ‘junk,’ has been shown by our work to carry out function y.” An example, from hundreds in the recent literature, follows below.

The Rational Course of Action

So what’s the rational course of action? you are asked. Forget about intelligent design. What, strictly pragmatically, is the best strategy for someone looking to make a discovery in genetics or genomics?

That’s easy, you say. Dig around in the bigger bin. That is where surprising genetic discoveries are waiting to be made.

Notice how this story bypasses the intelligent design controversy entirely. Even if someone were dead set against design being true, it would still be a better long-term research strategy, given the odds, to investigate apparently non-functional DNA for its possible roles in organisms.

We find people giving that advice from surprising places, such as the science writer Philip Ball, formerly a lead editor at the journal Nature. Now, Ball is no fan of intelligent design. The “dread concept” of design, as he describes ID in his fascinating new book How Life Works, counts among its ranks “vanishingly few mainstream scientists.” Ball proudly describes himself as “a materialistic believer in Darwinian evolution.” So, if we wanted to see his paid-up membership card in the Charles Darwin Got It Right Club, Ball could readily produce it from his wallet.

Ball Proposes a New Rule

Nonetheless, Ball is exasperated by junk DNA defenders who blithely assure the rest of the biological community that the non-functional portion of the human genome, to take an example close to home, can be fixed at 90 percent or thereabouts. The mindless processes of evolution, junk’s proponents say, are of course responsible for this huge putative junk percentage. As long as species continue to leave offspring, junk can accumulate in their genomes like so many cardboard boxes piling up in the attic, filled with school trophies and old sweaters.

Commenting on a remarkable new discovery, however, Ball finds — again — that DNA sequences “usually considered non-functional and [thus] discarded by sequence analysis programs” (here he quotes two Chinese biologists commenting on the same finding) actually belong in the treasure chest. The original research report, which showed the “junk” — i.e., microsatellite repeat sequences — to be functional, is open access here.

“This isn’t an isolated example,” grouses Ball, who, like other leading science writers, reads widely in the biological literature — far more widely, in fact, than most bench-bound researchers. Principal investigators consumed by securing their next grant and feeding their hungry postdocs and graduate students don’t have the luxury of deep dives into the journals. Ball does: that’s his day job. Run across enough results like those linked above, and one stops listening to the junk salesmen when they come by.

Finally, here is Ball’s proposed rule for molecular biologists: “stop assuming,” he writes, “we know which parts of DNA matter and which don’t.” Take another look in that waste bin.