Intelligent Design

Intelligent Design

Physics, Earth & Space

Physics, Earth & Space

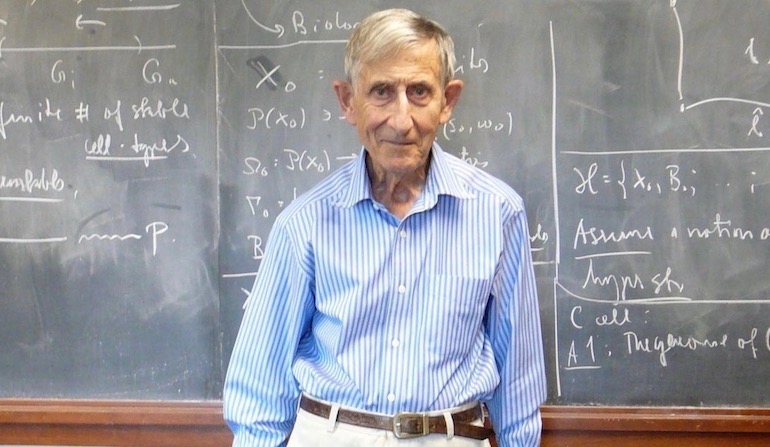

Freeman Dyson: The Passing of an Iconoclastic Physicist

Freeman Dyson, the theoretical physicist who worked with such luminaries as Richard Feynman, Hans Bethe and Edward Teller among others, died last week at age 96. This brilliant scientist never earned a PhD, a fact he was very proud of, and he was never awarded a Nobel Prize. During World War II, he worked for the Royal Air Force’s Bomber command to calculate the most effective bombing strategies. After the war he obtained a BA degree in mathematics from Trinity College, Cambridge.

He came to the U.S. at age 23 and began making an impact in physics by helping to unify quantum and electrodynamic theories into QED using Feynman diagrams. Some think this should have earned him a Nobel Prize in physics. J. Robert Oppenheimer gave Dyson a lifetime appointment at the Institute for Advanced Study starting in 1952. Unlike other physicists, he was not content to remain on one topic and plumb its depths. His interests ranged widely from mathematics to fundamental physics to space travel (Project Orion) to the origin of life to climate science. He discussed these topics in over a dozen books he authored.

A Subversive Thinker

Over the years, Dyson came to be known as a contrarian and even called himself subversive. He hated consensus thinking in science. I think it makes sense that a mathematical genius like Dyson should not be swayed by herd thinking. And, he was not afraid of expressing his views on non-scientific topics, including war, politics, rural poverty, and religion. He sometimes had quirky ways of approaching questions of science and policy. For example, his rejection of string theory, and his opposition to the superconducting supercollider and space telescope derive from his resistance to Big Science.

I share many of Dyson’s interests and even a few of the stances he took. I’ll focus on two here: climate change and intelligent design.

Climate Change

Dyson conducted climate research starting in the 1970s. He was aware of both the power and the limitations of climate models. In 2005 he began to publicly criticize the modern consensus on climate change/global warming and its effects, calling it an “obsession” and “a worldwide secular religion.” He described Al Gore as its “chief propagandist.” He believed that, on balance, rising carbon dioxide levels would likely be beneficial, due to its fertilization effects. This is an idea well supported by the evidence (see here and here). Not surprisingly, he was criticized for his stance. Another leading American physicist with similar views is William Happer.

Intelligent Design

As far as I know, Dyson never explicitly endorsed “intelligent design,” using precisely this phrase. However, I think it is clear from his writings that he did believe that nature is imbued with purpose. He wrote in Disturbing the Universe (1979), quoting Jacques Monod:

“The ancient covenant is in pieces; man knows at last that he is alone in universe’s unfeeling immensity, out of which he emerged only by chance.” I answer no. I believe in the covenant. It is true that we emerged in the universe by chance, but the idea of chance is itself only a cover for our ignorance. I do not feel like an alien in this universe. The more I examine the universe and study the details of its architecture, the more evidence I find that the universe in some sense must have known that we were coming. (p. 250)

He then goes on to describe several examples of fine-tuning in physics and cosmology known at the time. (For an updated treatment, see A Fortunate Universe: Life in a Finely Tuned Cosmos.) He continues:

I conclude from these accidents of physics and astronomy that the universe is an unexpectedly hospitable place for living creatures to make their home in. Being a scientist, trained in the habits of thought and language of the twentieth century rather than the eighteenth, I do not claim that the architecture of the universe proves the existence of God. I claim only that the architecture of the universe is consistent with the hypothesis that mind plays an essential role in its functioning. (p. 251)

In his acceptance speech for the Templeton Prize in 2000, he said:

My personal theology is described in the Gifford lectures that I gave at Aberdeen in Scotland in 1985, published under the title, Infinite In All Directions. Here is a brief summary of my thinking. The universe shows evidence of the operations of mind on three levels. The first level is elementary physical processes, as we see them when we study atoms in the laboratory. The second level is our direct human experience of our own consciousness. The third level is the universe as a whole. Atoms in the laboratory are weird stuff, behaving like active agents rather than inert substances. They make unpredictable choices between alternative possibilities according to the laws of quantum mechanics. It appears that mind, as manifested by the capacity to make choices, is to some extent inherent in every atom. The universe as a whole is also weird, with laws of nature that make it hospitable to the growth of mind. I do not make any clear distinction between mind and God. God is what mind becomes when it has passed beyond the scale of our comprehension. God may be either a world-soul or a collection of world-souls. So I am thinking that atoms and humans and God may have minds that differ in degree but not in kind. We stand, in a manner of speaking, midway between the unpredictability of atoms and the unpredictability of God. Atoms are small pieces of our mental apparatus, and we are small pieces of God’s mental apparatus. Our minds may receive inputs equally from atoms and from God. This view of our place in the cosmos may not be true, but it is compatible with the active nature of atoms as revealed in the experiments of modern physics. I don’t say that this personal theology is supported or proved by scientific evidence. I only say that it is consistent with scientific evidence. [Emphasis added.]

Follow the Evidence

In these quotes and in others writings, Dyson was careful to take an open-minded approach: not fully endorsing design, yet not rejecting it either. Follow the evidence; prepare to be surprised.

Dyson’s personal theology is certainly unusual, a species of scientific theology similar to Frank Tipler’s with elements of pantheism (if you want to put labels on it). He called himself a practicing Christian but not a believing Christian. His heterodox religious views fit well with his iconoclastic scientific thinking. Of course, none of this matters much when it comes to the concept of intelligent design, since the locus of the designing intelligence is not so important as the fact that there is one.