Evolution

Evolution

Intelligent Design

Intelligent Design

Science Versus the Oldest Anti-Intelligent-Design Argument

Sometimes, science moves in great leaps and bounds. At other times, it seems to move at a snail’s pace, with the same questions debated ad nauseum for millennia. The latter is the case for one of the oldest anti-design arguments. It was proposed more than two millennia ago, and it is still debated in the 21st century. But now, the final resolution may be in sight.

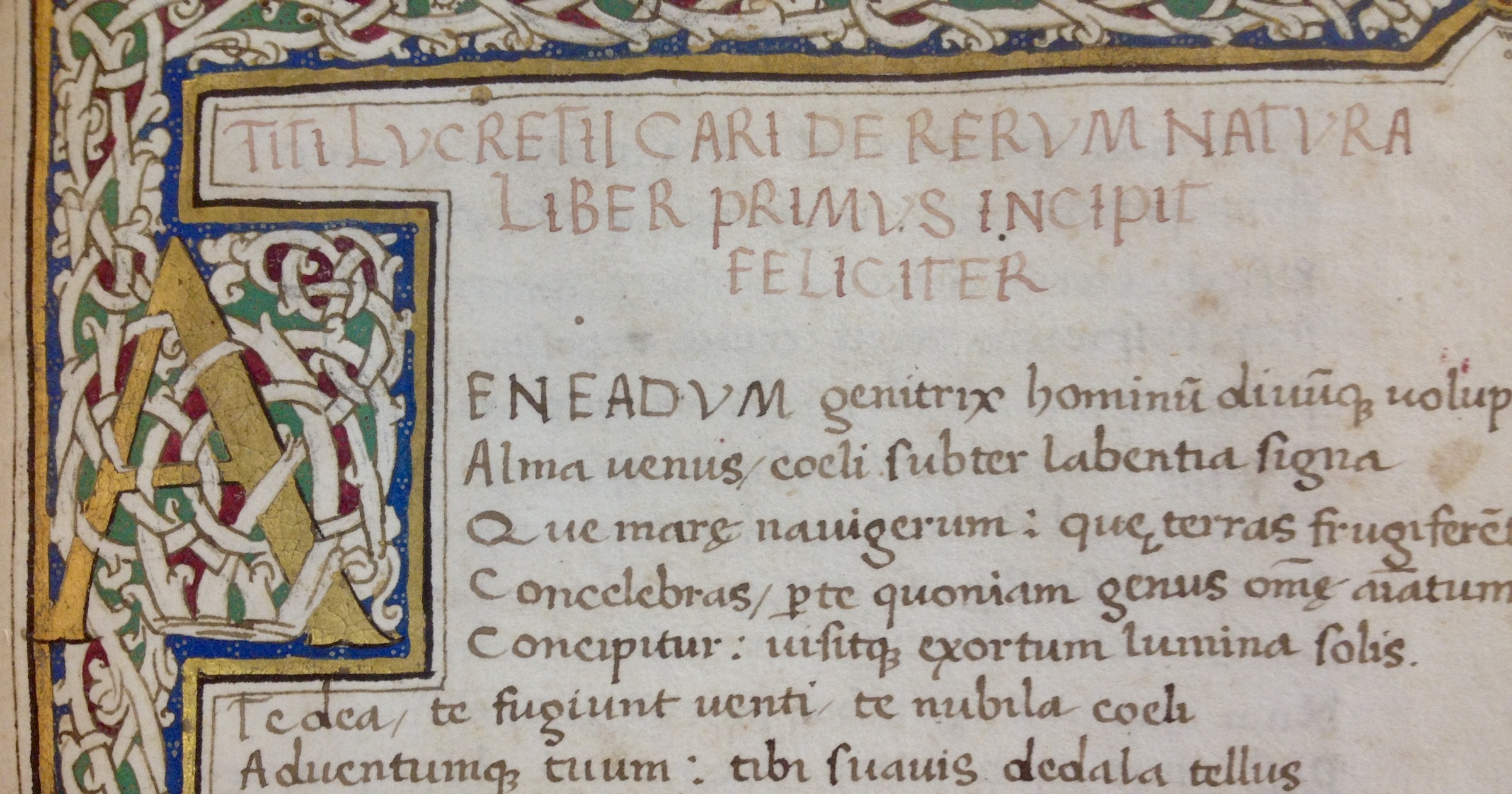

The argument was perhaps first made by the Greek philosopher Epicurus. Most of his own writings do not survive, so the most influential presentation of the ideas is the beautiful Latin poem On the Nature of Things written by the Epicurean philosopher Lucretius. Here is how Lucretius sums up the argument:

Neither by counsel did the primal germs [atoms]

‘Stablish themselves, as by keen act of mind,

Each in its proper place; nor did they make,

Forsooth, a compact how each germ should move;

But since, being many and changed in many modes

Along the All, they’re driven abroad and vexed

By blow on blow, even from all time of old,

They thus at last, after attempting all

The kinds of motion and conjoining, come

Into those great arrangements out of which

This sum of things established is create,

By which, moreover, through the mighty years,

It is preserved, when once it has been thrown

Into the proper motions, bringing to pass

That ever the streams refresh the greedy main

With river-waves abounding, and that earth,

Lapped in warm exhalations of the sun,

Renews her broods, and that the lusty race

Of breathing creatures bears and blooms, and that

The gliding fires of ether are alive —

What still the primal germs nowise could do,

Unless from out the infinite of space

Could come supply of matter, whence in season

They’re wont whatever losses to repair.

Translation: Everything that exists was made not by intelligent design, but rather by the random arrangement and rearrangement of atoms. Since the universe is infinite, there are enough opportunities for every possible arrangement of atoms to occur eventually, even the most unlikely. Our world, and the life on it, is one of those unlikely (but eventually inevitable) arrangements.

Epicurus Benched

It is a clever argument, since it does in fact explain how specified complexity could emerge without design. But there is something unsatisfying about it. It seems to explain too much. After all, if one technically possible freakish fluke is inevitable in an infinite universe, so is any other. Doppelgangers of Epicurus? Check. Infinite copies of New York City? Check. A one-second-old brain full of false memories? Check. The argument seems to completely undermine the intelligibility of the universe.

What was needed for materialist naturalism to really take over Western thought was a theory that would explain life within the framework of an orderly and comprehensible universe. Charles Darwin’s theory seemed to fit the bill. His mechanism of random variation and natural selection seemed to show that the development of complex life was probable on any planet, given a self-reproducing system to start with. Here was an explanation that only explained what it was supposed to explain, no mad monstrosities or absurd possible worlds. Nice and tidy.

Nevertheless, the older argument never really went away. So, when skeptical theorists pointed out situations where Darwin’s stepwise mechanism shouldn’t apply — such as the origin of the first self-replicating system, or the many cases where multiple random changes are needed to provide a single adaptive feature — Epicurus’ argument could still be invoked: given enough time and/or space, surely the necessary arrangement of atoms would turn up somewhere.

Thus, the Epicurean argument lived on as a fallback to explain whatever Darwin’s theory couldn’t. This is still the state of the debate today. Last month, for example, I had a discussion with a biologist who pointed to the “ca. 4 billion years of life on Earth” to dismiss Michael Behe’s irreducible complexity argument.

A Crumbling Foundation

But the old fallback is not as reliable as it once seemed. The first crack was the discovery of cosmic expansion, just a few decades after Darwin proposed his theory. After more than two thousand years of Epicurean influence, and contrary to the assurances of mainstream physicists at the time, it turned out that the universe was not eternal, and probably not infinite. That meant it was no longer a given that any improbability could be explained by the sheer size and age of the universe.

However, the universe was still really old, and really big. It seemed safe to assume it was still big and old enough to deal with any inconvenient improbabilities.

But new discoveries seem to have finished what the Big Bang theory started. It is becoming increasingly undeniable that the building blocks of life are far too unlikely to emerge by chance even in a universe as large and old as ours.

For example, theoretical biologist Stuart Kauffman and University of Bologna biotechnologist and computer scientist Andrea Roli argue in a new paper in the volume Evolution “On Purpose” that biology is not reducible to physics, even in theory, because the number of possible arrangements of atoms far exceeds the number of arrangements that could ever have occurred in the lifespan of the universe. Life, in other words, is not a given. Kauffman and Roli write:

The universe is not ergodic above the level of about 500 Daltons (Kauffman et al., 2020). The universe really will not make all possible complex molecules such as proteins 200 amino acids long in vastly longer than the lifetime of the universe (Kauffman, 2019; Cortês et al., 2022). Because the universe is not ergodic on time scales very much longer than the lifetime of the universe, it is true that most complex things will never get to exist.

The word “ergodic” refers to the likelihood of something recurring by chance. If you add more time to a system, more of it can be ergodic; something might not be likely to happen in one year, but very likely to happen in one billion years. Likewise, if you add more space, more of the system will be ergodic, because there are more opportunities for any possible eventuality to occur.

If the universe is only ergodic below 500 Daltons, that means that on average only arrangements of matter with masses less than 500 Daltons are individually likely to happen by chance in the 13.7 billion year history of the universe. Larger structures are individually unlikely by chance, because there are simply more ways to arrange matter than would be covered even in all of time and space.

500 Daltons is not a very high threshold. For comparison, the average amino acid has a mass of around 100 Daltons. That means that that unusual large structures — like many of the proteins that make the basic machinery of life — cannot be explained as lucky occurrences.1 And yet those proteins are the very building blocks needed to make Darwinian evolution work.

Not Surprising

And so one of the oldest argument against design falls apart. This is not surprising, since the universe does not appear to be infinite; and Lucretius himself admitted that without infinite opportunities, you would not expect complex life to form.

This is significant because although Epicurus has been mostly relegated to the bench for the last century and a half in favor of the new star player, his argument has really always been the foundation of naturalism. Darwin’s explanation is too contingent — it’s not the universal explanation that the anti-design naturalist needs. Our world and its inhabitants are so patently strange that there are really only two satisfying explanations for how we came to exist: that we were made this way on purpose, or that we are merely one lucky fluke in an infinite (or practically infinite) universe.

As we learn more about the universe, we can finally test those two theories against observation. Do we see an infinite sea of worlds within the universe, containing every possible outcome? Or not? Epicurus’ hypothesis results in predictions, which can turn out to be true, or untrue. (Of course, if we failed to observe Epicurus’ infinite universe, you could propose that it exists off in some unobservable other realm. But, in the framework of observational science, that would be to admit defeat, wouldn’t it?)

For a long time, Epicurus’ version of the universe seemed probable to many. After natural philosophers realized how vast the universe really was, and again after the existence of atoms was confirmed, Epicurus seemed to be vindicated. But now, we have discovered that however vast the universe may be, it is finite, and its size does not hold a candle to the vast improbability of the miracle that is life. After more than 2,000 years, the original foundation of materialist naturalism in Western thought seems to be crumbling. The question is: how long will it take for the worldview built on that foundation to crumble too?

Notes

- Intelligent design advocate Douglas Axe made a similar argument about the unlikeliness of proteins in his 2016 popular treatment Undeniable, based on peer-reviewed research on protein folding he conducted at Cambridge in the early 2000s. But Kauffman and Roli avoid citing him in their review, for some reason. (On reflection, it was probably a wise decision.)